Poolish

Those who have out of desire have chosen to or out of dire necessity been forced to bake their own bread may have encountered the term poolish. It refers to a semi-liquid pre-ferment used in bread-making, a mixture of half water and half white flour mixed with a teeny bit of yeast and allowed to slowly ferment for several hours, up to a day, before mixing up the final dough.

The word itself is an exceedingly odd one, and has been the source of much head-scratching and inconclusive speculation among bread-bakers across the world: it looks like the English word Polish, but is spelled funny, and anyway seems to be borrowed from French, where the spelling would be funnier still. Most discussions of the technique include the obligatory etymological digression, usually fantastical, involving journeymen Polish bakers fanning out over Europe. Linguists too have gotten on the trail: David Gold’s Studies in Etymology and Etiology (2009) devotes a whole page to the question, but does not get too far.

In its current form it is technical jargon from French commercial baking, and has probably made its way to a broader public through Raymond Calvel’s influential Le gout du pain (‘The taste of bread’) from 1990. In his account:

This method of breadmaking was first developed in Poland during the 1840s, from whence its name. It was then used in Vienna by Viennese bakers, and it was during this same period that it became known in France. (2001 edition translated by Ronald Wirtz)

This explanation has been widely accepted, and appears in one form or another in any number of bread-baking books. But how could it even be true? The first problem is the word itself. Poolish is not the French word for Polish, and doesn’t much look a French word anyway. In earlier French texts it crops as pouliche, which looks more French and is indeed the word for a young mare, whose connection to bread dough is tenuous at best. But earlier French texts also have the spelling poolisch or polisch, which looks rather more German than French and suggests we follow the Viennese trail instead.

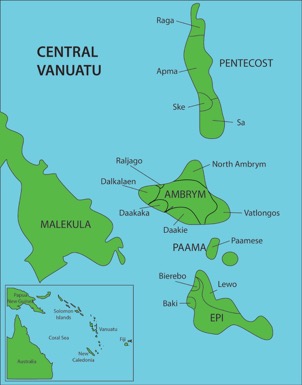

This thread of inquiry has its own potential hiccoughs. The German word for Polish is polnisch, with an [n], so would this not just be fudging things? Actually not: polisch, poolisch, pohlisch or pollisch turn up often enough in older texts as alternative words for ‘Polish’, particularly in southern varieties of German that include Austria. And it is exactly in these form that we find it being used to refer to this particular process, juxtaposed with Dampfl (or Dampfel or Dampel), the term in southern Germany and Austria for a rather stiffer pre-ferment which goes through a shorter rising period, as in these two examples from 1865, one from Leopold Wimmer’s self-published advertising advertising screed for St. Marxer brand (of Vienna) pressed yeast, where it turns up as Pohlisch:

![]()

the other from Ignaz Reich’s (of Pest, as in Budapest) account of ancient Hebrew baking practices, where it’s rendered as pollisch.

![]()

The term polisch (in all its variants) in this sense seems to have died a natural death in German, only to reemerge during the current craft-baking revival in the guise of poolish.

But if poolish was originally the (or a) German word for Polish, we run up against the sticky question of what it was actually referring to. Calvel repeats the story that this technique was invented by Polish bakers (which turns up in a 1972 article in The Atlantic Monthly, I think anyway, because it’s but coyly revealed by Google in snippet view), a supposition which lacks as much plausibility as it does historical attestation. Poland has traditionally been a land of sourdough rye bread. Is seems unlikely that a novel technique involving the use both of white wheat flour and commercial pressed yeast (a relatively new product) would have been devised there and introduced into the imperial capital that was Vienna. So what on earth could it have meant?

Here I make my own foray into speculation; you read it here first. Poland is not just a land of sourdough rye bread, it is a land of a soup made from rye sourdough: żur or żurek (itself derived from sur, one variant of the German word for ‘sour’), still widely consumed and also sold in ready form form for time-strapped gourmands. Since the Austro-Hungarian Empire included much of what had once been Poland, it isn’t too far-fetched to think that people in Vienna might have been familiar with this soup. And since the salient characteristic of poolish is that it is basically liquid, in opposition to more solid doughs, my guess is that the term poolish arose as a facetious allusion to żur: a soup-like fermenting dough mixture, like the thinned-out sourdough soup that Poles eat.

Here I make my own foray into speculation; you read it here first. Poland is not just a land of sourdough rye bread, it is a land of a soup made from rye sourdough: żur or żurek (itself derived from sur, one variant of the German word for ‘sour’), still widely consumed and also sold in ready form form for time-strapped gourmands. Since the Austro-Hungarian Empire included much of what had once been Poland, it isn’t too far-fetched to think that people in Vienna might have been familiar with this soup. And since the salient characteristic of poolish is that it is basically liquid, in opposition to more solid doughs, my guess is that the term poolish arose as a facetious allusion to żur: a soup-like fermenting dough mixture, like the thinned-out sourdough soup that Poles eat.

This theory has the minor drawback of lacking any positive evidence in its favor. So far the only 19th century reference to żur outside of its normal context that I have been able to find is as a cure for equine distemper, otherwise known as ‘strangles’. That leads us into the topic of pluralia tantum disease names…

Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well.

Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well. James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew:

James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew: Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions:

Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions: Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where

Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)

Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)