A “let’s circle back” guy

As everyone knows by now, for the foreseeable future we must all stay at home as much as possible to slow the spread of COVID-19 and reduce the burden on our health services – which has already been substantial, and will soon be enormous even in the best possible scenario.

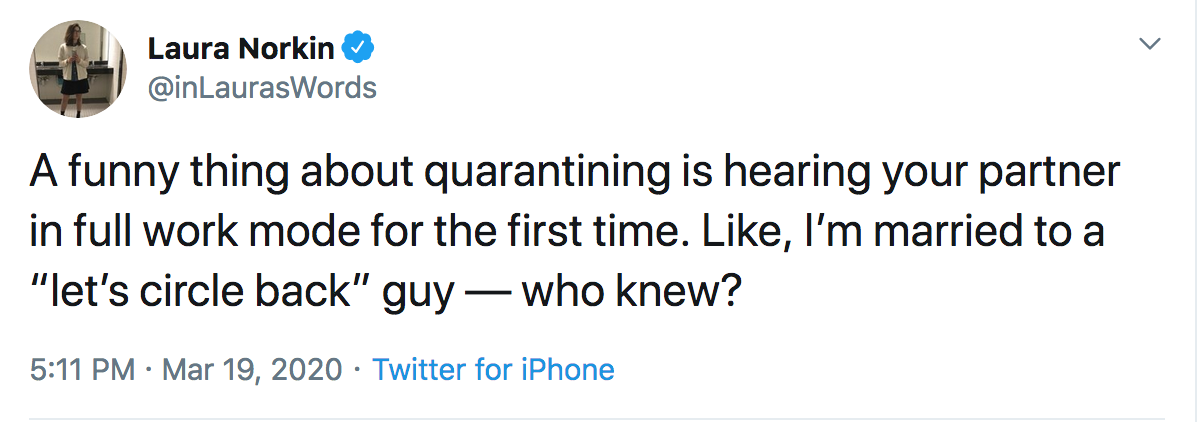

This shift in the way we operate as a society will have a wide range of effects on our lives, which are already being noticed. Some of these were the kind of thing you might have thought of in advance – but others less so. For example, soon after the advice to work from home really started to bite in the US, a substantial thread developed on Twitter, all started off by the following tweet:

The thousands of responses that appeared within a few hours of this tweet shows how deeply it resonated: many people must have been through their own version of the same surprising experience, some of them presumably in the last few days. But what happened here, and why was it so surprising? And why, as a linguist, am I sitting at home and writing a blog post about it now?

This single tweet, which people found so easy to identify with, in fact brings together a number of issues that linguists are interested in. For one thing, it works as a clear illustration of a point that people intuitively appreciate, but which has endless ramifications: the language you use is never just an instrument for communicating your thoughts, but is also taken to say something important about your identity, whether you intend it to or not. If a guy uses the expression “let’s circle back”, meaning to return to an issue later, that makes him a “let’s circle back” guy – that is, a particular kind of person. In a jokey way, the tweeter is implying that she already had a mental category of ‘the kind of person who would say things like that’, and she takes it for granted that we do too. In this case, the surprise for Laura Norkin was in suddenly discovering that her own husband belonged in that pre-existing category: the way she tells it, hearing him use a specific turn of phrase counted as finding out important new information about who he is as a person, which she was not necessarily best pleased about.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the field of sociolinguistics has drawn attention to the fact that this kind of thing is going on everywhere in language. Consciously or unconsciously, people are making linguistic choices all the time – whether that means choosing between two totally different languages, between two different expressions with the same meaning (do you circle back to something or just return to it?), or between two very slightly different pronunciations of the same word. Any of these choices might turn out to ‘say something’ about how you see yourself – or how other people see you. And the social meanings and values assigned to the different choices are likely to change over time: so understanding what is going on with one person’s use of language really requires you to understand what is going on right across the community, which is like an ecosystem full of co-existing language diversity. How do linguistic developments, and the social responses to them, propagate and interact in this ecosystem? That’s something that researchers work hard to find out.

The tweet also picks up on the importance of the situational context for the way people use language. Laura Norkin had never heard her husband use the offending expression before because it belongs to a particular register – meaning a variety of language which is characteristic of a particular sphere of activity. Circling back is characteristic of ‘full work mode’, something which had never previously needed to surface in the domestic setting.

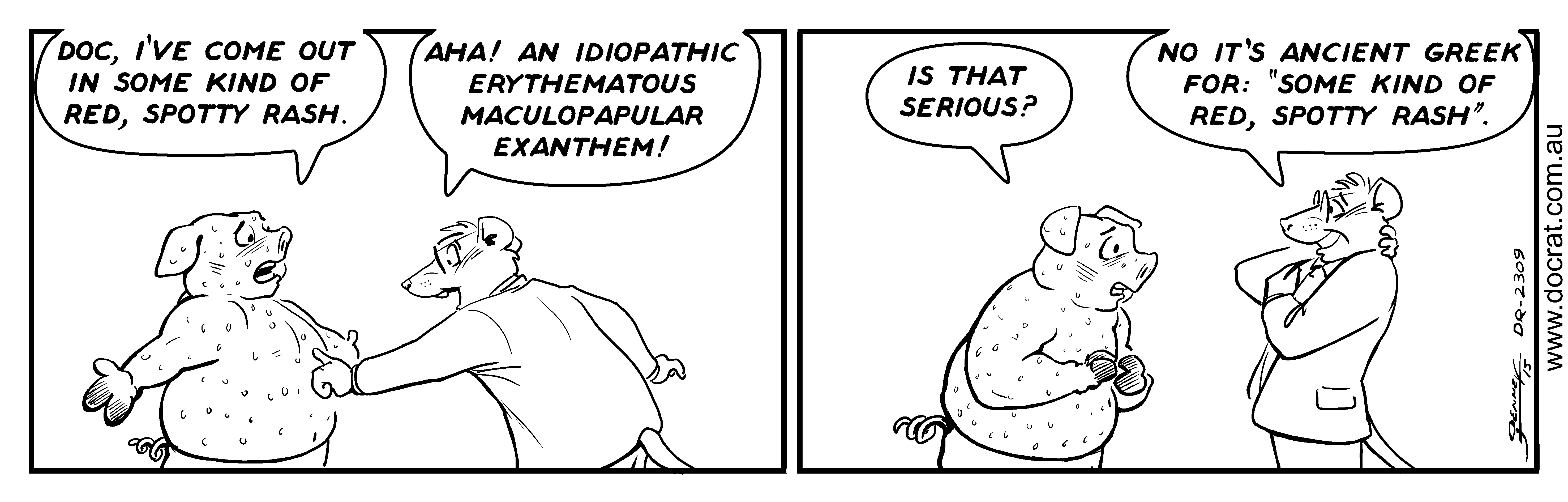

Why do registers exist? Partly it must be to do with the fact that different people know different things: for example, lawyers can expect to be able to use technical legal terminology with their colleagues, but not with their clients, even if they are talking about all the same issues – because behind the terminology there lies a wealth of specialist knowledge. Similarly, anyone would modify their language when talking to a five-year-old as opposed to a fifty-year-old.

But this cannot be the whole story: it doesn’t help you to explain the difference between returning and circling back. Should we think of the business/marketing/management world, where terms like circling back are stereotypically used, as a mini community within the community, with its own ideas of what counts as normal linguistic practice? Or is everyone involved giving a signal that they take on a new, businesslike identity when they turn up to the office – even if these days that doesn’t involve leaving the house? Again, working out the relationship between the language aspect and the social aspect here makes an interesting challenge for linguistics.

But this was not just an anecdote about how unusual it is to be at home and yet hear terms that usually turn up at work. We can tell that “let’s circle back”, just like other commonly mocked corporate expressions such as “blue-sky thinking” or “push the envelope”, is something we are expected to dislike – but why? The existence of different registers is not generally thought of as a bad thing in itself. You could give the answer that this expression is overused, a cliché, and thus sounds ugly. But really, things must be the other way round: English abounds in commonly used expressions, and only the ones that ‘sound ugly’ get labelled as overused clichés. And there is nothing inherently worse about circle back than about re-turn – in fact, when you think about it, they are just minor variations on the same metaphor.

So what is really going on here? The popular reaction to circle back, and other things of that kind, seems to involve lots of factors at once. The expression is new enough that people still notice it; but it is not unusual enough to sound novel or imaginative. It is currently restricted to a particular kind of professional setting that most people never find themselves in; but it does not refer to a complex or specific enough concept to ‘deserve’ to exist as a technical term. And we do not tend to worry too much about making fun of the linguistic habits of people who have a relatively privileged position in society: certainly, teasing your husband by outing him as a “let’s circle back” guy is not really going to do him any harm.

Spelling it out like this helps to suggest just how much information we are factoring in whenever we react to the linguistic behaviour of the people around us – and this is something we do all the time, mostly without even noticing. We are social beings, and cannot help looking for the social message in the things people say, as well as the literal message: establishing this fact, and working out how to investigate it scientifically, has been one of the great overarching projects of modern linguistics. Right now, for everyone’s benefit, we need to learn how to be less sociable than ever. But as the tweet above suggests, people’s inbuilt sensitivity to language as a social code is not going to change any time soon.