Entree

One of the peculiar habits that strikes a foreign visitor to a restaurant in the US (alongside heaps of ice in your drink and the sneaky habit of leaving sales tax off the price) is that menus typically list main course dishes as ‘entrees’. But ‘entrée’ is a French word that means something like ‘entry’ or ‘entrance’, so shouldn’t it be the same thing as appetizer or hors-d’oeuvre or starter? It seems like some fundamental misunderstanding of the term, like the rectangular chocolate ‘croissants’ shamelessly marketed outside of France.

Well, yes and no. As an American I feel duty-bound to show that there is a systematic and logical explanation to how we got here, and that it’s not just people being, well, confused. Partly it’s a story of how word meanings change over time, but it’s also a story of how the things words refer to themselves change to the point of unrecognizability.

Things start in France, of course, as well summarized by Dan Jurafsky:

[…] the word entrée originally (in 1555) meant the opening course of a meal, one consisting of substantial hot ‘made’ meat dishes, usually with a sauce, then evolved to mean the same kind of dishes, but served as a third course after a soup and a fish, and before a roast fowl course. American usage kept this sense of a substantial meat course, and as distinct roast and fish courses dropped away from popular usage, the meaning of entree in American English was no longer opposed to fish or roast dishes, leaving the entree as the single main course.

Jurafsky dates the shift in meaning to sometime between the 30s and the 50s, and identifies it as a particularly American phenomenon. In fact, the change appears to have started considerably earlier, and not just in North America. The secret of entrée’s success seems to have been its inclusiveness: fish is fish, roast is roast, but an entrée could be pretty much anything. A 1908 issue of Good Housekeeping tells us:

An entree is often but a Made-up dish of leftovers, palatable and attractive, or it is a little more complicated way of serving an ordinary dish so that it can take the place of an entire course. All made dishes, therefore, are not entrees; they are only such when served as the main part of a course. So if one serves any complicated dish with a main dish of meat or poultry or fish, or even with a salad, it is not then called an entree, but a side dish.

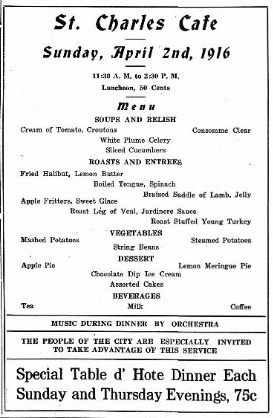

By 1916 the St. Charles Café in Dickinson, North Dakota combines entrees and roasts in a single course:

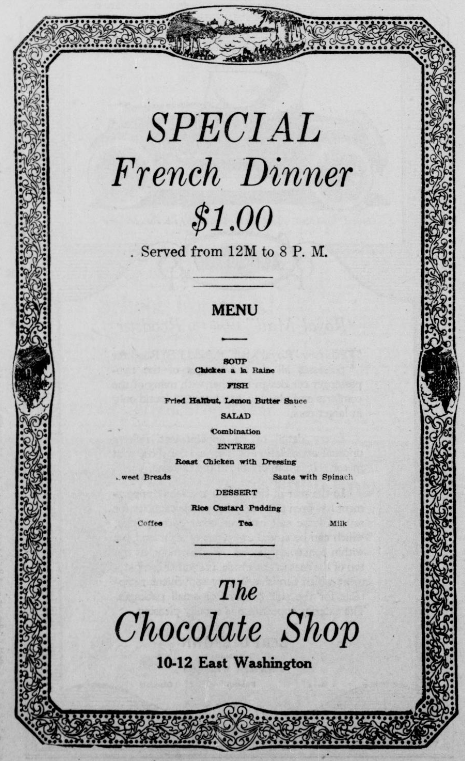

And by 1919 the Chocolate Shop in Phoenix, Arizona offers a Special French Dinner with an entrée as the centerpiece, subsuming the roast:

By 1928 fortunate diners could treat themselves to an entire meal based on Jell-O, with a Chicken Mouse as the entrée, squeezed between Jell-O Fruit Cocktail and Jell-O Salad Supreme.

Meanwhile, in Australia things went quite a different route. There, the entrée really has become the first course appetizer. Could this be the result of taking things too literally, like when people think that sugarplums — pretty much a forgotten food — were actually made from plums? This would then be a kind of folk etymology — the reinterpretation of the meaning of a word on the basis of what it looks like it ought to mean (and a topic well worth a separate post).

I think though the story may be rather different; at least that’s what I gather from exploring old issues of The Australian Women’s Weekly. The key date seems to be 1968. Before that, menus were structured either in the traditional way (with entrée following soup and preceding the main course) or in the ‘American’ way (‘a three-course dinner of soup or fruit cocktail, roast or entrée, and sweets or ice-cream and coffee…’ — from 1942). But in 1968 we find these competing orders in different issues:

traditional: pre-dinner drinks, hors-d’oeuvre, soup, entrée, main course, dessert, demitasse

innovative: pre-dinner drinks, hors-d’oeuvre, entrée, soup, main course, dessert, demitasse

That is, the entrée has shifted to being before the soup, immediately next to the hors-d’oeuvre. This, I hazard to guess, is the origin of the Australian state of affairs: a change in menu planning brought these two otherwise similar courses in direct contact, and they merged. (If The Australian Women’s Weekly can be taken as representative of Australian society as a whole.)

In France meanwhile, the entrée seems to have gone the same route as in Australia, and now occupies a position somewhere towards the beginning of the meal. Jurafsky suggests that this was indeed a kind of folk etymology, since the ‘real’ meaning of entrée is pretty obvious in French. But if the (admittedly scanty, so far) Australian evidence is any indication, the “obvious” explanation may not be the correct one. Rather, it could well be a post-hoc justification. In any case, it does leave American English as the outlier.

Or does it? The dictionary of the French Academy will have none of this. In its entry under entrée, alongside the more-or-less classic definition (‘Mets qui vient après les hors-d’œuvre et précède le plat principal’ [dishes which come after the hors-d’oeuvre and precede the main dish]) it adds ‘Par ext. Plat principal. Un repas composé d’un hors-d’œuvre, une entrée et un dessert.’ [By extension: main dish. A meal consisting of an hors-d’oeuvre, an entrée and a dessert]. In other words, just like our Jell-O meal of 1928. Perhaps American usage isn’t so peculiar after all. But this flies in the face of contemporary French usage. That may be par for the course for the French Academy Dictionary, but one does wonder what usage this definition is actually reflecting. This suggests the semantic development of the word has been far more complex than is apparent on the surface. Some serious archival work is in order…