History on the Ground

Linguists spend most of the year stuck to the computer monitor: analyzing data, reading, or writing papers. But the time comes when we have to roll up our sleeves and find our sense of adventure. Personally, this is my favorite time of the year! Going on a linguistic field trip often involves living in a local community and immersing yourself in a completely different culture. You learn so much about the customs, traditions, beliefs… And, of course, you learn a lot about the language.

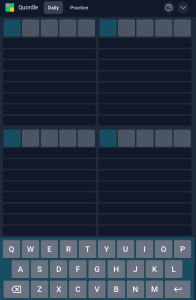

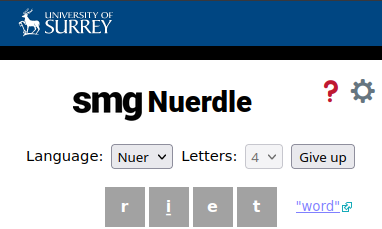

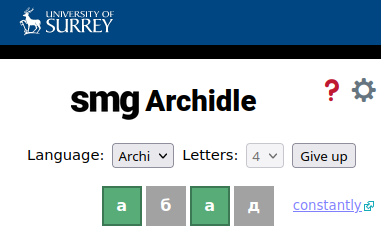

Linguistic field trips are essential for researchers who work with poorly documented languages. We prepare questionnaires, design experiments, and go to the local community to collect data that we need for our research. Here, at SMG, we do fieldwork a lot. You can get a glimpse of this fascinating part of a linguist’s life in some of the previous posts. Check out, for example, this beautiful piece on Archi, this account of cultural and language diversity in the South Pacific, and the most recent post about intricate ways to express respect in Vanuatu.

However, there seems to be a limitation. What should you do if you study the history of some phenomenon? If you are not only interested in how the system is now, but also in how it was before? We cannot jump into a time machine and reemerge in the 15th-century world to run our questionnaires there. So surely historical texts and comparative grammars are the only way to go, and fieldwork is not useful here… Or is it? Well, it turns out that a field trip can be very helpful for extrapolating historical data, but only if you are lucky with the location. Fortunately, I am!

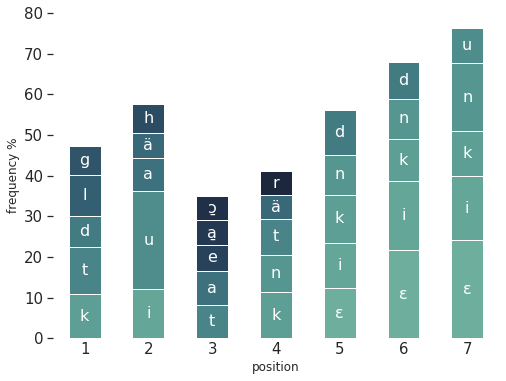

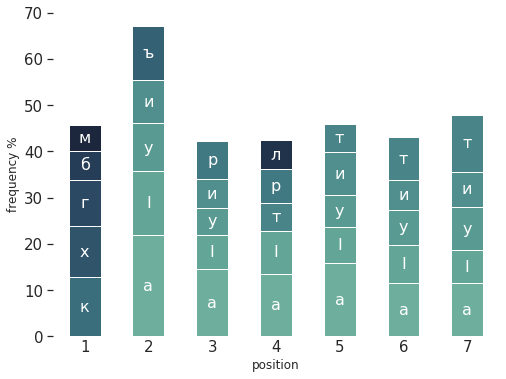

In the project “Declining case: Inflectional loss in progress”, my colleagues and I study dialects of Serbian and Bulgarian. These two languages have been posing linguists a headache for more than a century already. Although they are quite closely related and are spoken side by side, they have a lot of significant differences in the grammatical structure. To name some, (1) Bulgarian has articles (like English a and the), while Serbian does not, (2) Serbian uses infinitives, while Bulgarian does not, and (3) Serbian nouns have a fully-fledged morphological case system, while Bulgarian nouns do not inflect for case at all. People still argue about the exact reasons for this, but there is a general consensus that Bulgarian has undergone certain changes because it is located in the so-called Balkan linguistic area. A cool thing is that there is no sharp border between the innovative grammatical system of Bulgarian and the conservative system of Serbian. Rather, in the geographical zone on both sides of the Serbian-Bulgarian border, we see a variety of intermediate systems.

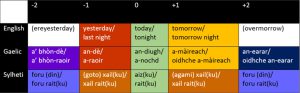

Let us see how it works on the example of the case inflection, which we study in our project. Cases are used in some languages to mark grammatical relations, such as subject or object. Serbian does it in this way, while Bulgarian uses prepositions instead. Take a look at this table, where the word ‘Cyprus’ appears in different contexts. See how in Serbian this word changes the ending depending on the context and in Bulgarian it keeps the same form? Just like in English!

| Serbian | Bulgarian | Translation |

| vole Kipar | xaresvat Kipâr | ‘They like Cyprus’ |

| stanovništvo Kipra | naselenieto na Kipâr | ‘The population of Cyprus’ |

| pomažu Kipru | pomagat na Kipâr | ‘They help Cyprus’ |

| upravljaju Kiprom | upravljat Kipâr | ‘They govern in Cyprus’ |

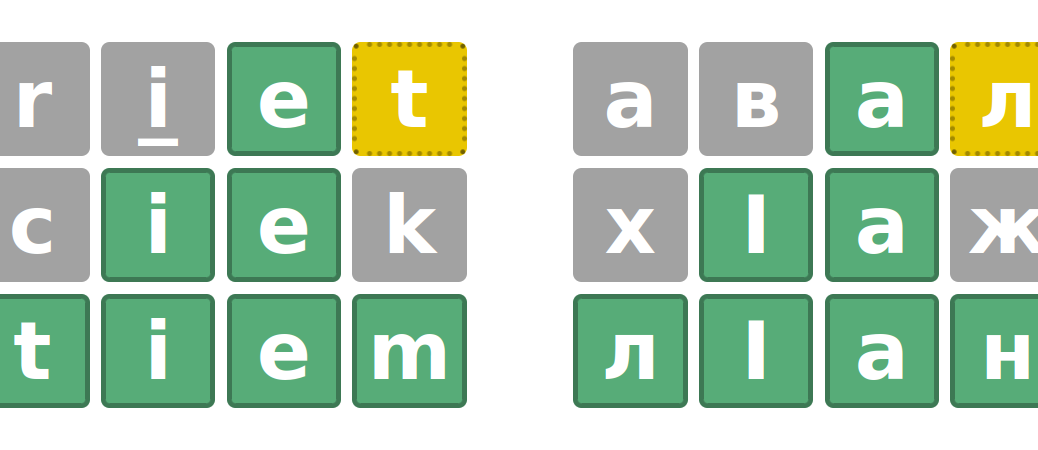

Overall, Serbian has six cases, while Bulgarian uses one general case form. So, what do we see in the transitional zone? Well, depending on where exactly we look, we find different systems. For example, in a more western part of the transitional area, we can meet a system where they use three cases, while in a more eastern part we can find a two-case system.

| Serbian | Transitional system 1 | Transitional system 2 | Bulgarian |

| Case 1 | Case 1 | Case 1 | No case |

| Case 2 | Case 2 | Case 2 | |

| Case 3 | Case 3 | ||

| Case 4 | |||

| Case 5 | |||

| Case 6 | |||

What does it mean? It looks like standard Bulgarian at some point in its development lost its case marking on nouns completely, while the dialects in the transitional zone underwent this change to a smaller degree. The further west we move, the less this change affected the dialect. This situation created an unprecedented opportunity for us. We can go to different places in the transitional zone, compare their systems to each other, and use this comparison to create a historical model of the loss of case. We do not need a time machine, we have the different stages of this process living side by side today!

This summer, for example, I went to the municipality of Brus, which is located in Southern Serbia. There I witnessed the initial stages of case decline. People in Brus still use all six cases, but sometimes replace one with another, or insert a preposition in phrases where standard Serbian would not have it. While interviewing people, I learned about some fascinating traditions in this area. For example, one of the oldest customs at the wedding is to put an apple at the highest point in the backyard, and the groom has to hit the apple with a gun. If he fails to do so, he is not going to get his bride!

Apparently, in earlier times, a wedding would last for several days and involve all sorts of rituals. Unfortunately, most of them are lost now. It would be so nice to see how a wedding was celebrated then! But for this, I am afraid, we do need a time machine.