Happy Christmas/Nowell/Yule/etc.

It might have escaped your notice, but Christmas is coming! While the exact date of the birth of Jesus Christ is subject to some debate, the overall consensus of the early church settled upon sometime in winter as the time to hold the feast. However, Christian denominations still disagree on the exact date of the celebration; in the West Christians celebrate on the (Gregorian) 25th December, but some Orthodox churches (notably the Russians) retain the Julian Calendar, so their liturgical 25th December is in fact the 7th January in the Gregorian calendar. Meanwhile, the Armenians have long observed the 6th January as their Christmas, whether that be the Gregorian 6th January as in Armenia or the Julian 6th January (Gregorian 19th) as the Armenians of Jerusalem still do. With such a level of disagreement about when to celebrate, it is no surprise that there is even more disagreement about what the feast should even be called.

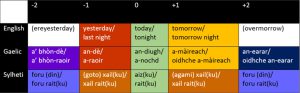

English is simple enough; since Old English the term Christes mæsse ‘Christ’s mass’, referring to the actual religious service held on the day, came to refer to the whole festive period. A similar process happened to give Dutch Kerstmis. On the other hand, English also have the term Nowell (think of the carol ‘The First Nowell’), which is borrowed from the French term Noël.

This French term is one of an array of terms in romance languages derived from Latin nātālis, meaning ‘birthday [of Christ]’. This also provides us with Portugues Natal, Catalan Nadal and Italian Natale. Spanish meanwhile uses Navidad, which comes from a related Latin term nātīvitās. Another Latin term nātālīcia ‘birthday feast’ was an early borrowing into the Celtic languages, giving for example Welsh Nadolig and Gaelic Nollaig, while Albanian borrowed a Latin phrase Christī nātāle, which with Albanian’s complicated history ended up as Kërshëndella. Greek Khristougenna also means ‘Christ’s birth’; Church Slavonic likewise boasted a form Rozhdestvo (fully Rozhdestvo Khristovo), again meaning ‘birth [of Christ]’, which is now the Russian form as well, while Polish combines a derivative of that same root with the Slavic Bog ‘God’ to give Boże Narodzenie ‘birth of Godˈ.

A different Latin term, calendae, originally meaning ‘Kalend (the first day of the month)’, which also gives us English calendar, also ended up being borrowed into Proto-Slavic as *kolęda, with many Slavic languages using this as an alternative term for ‘Christmas’ (somewhat akin to referring to Christmas as Yule in English, on which more later); in Bulgarian Koleda is the primary term, and Lithuanian also refers to the festival as Kalėdos, borrowing from the Slavic (Latvian Ziemassvētki simply means ‘winter holidays’). Furthermore, a Polish kolęda and a Russian kolyadka are both Christmas carols, as is a colindă in Romanian.

A third term that English has is Yule. This is a Germanic term, likely referring to festivities in general, but now the word for Christmas in modern Scandinavian languages, e.g. Danish/Swedish/Norwegian Jul and Icealandic Jól. This word also spread to other languages in Scandinavia, hence Finnish Joulu (If you visit actual Lappland ‘Father Christmas’ will be referred to Joulupukki ‘Christmas Buck’), alongside the more archaic juhla, a general word for ‘party, celebration’, while (Northern) Sámi has Juovllat from the same source. German Weihnachten, meanwhile, originally meant ‘Holy Nights’; Czech Vánoce/Slovak Vianoce are borrowed from the German, replacing Germanic Nacht with Slavic noc for ‘night’.

Perhaps the most interesting pair of terms for Christmas are Romanian Crăciun and Hungarian Karácsony. These terms are likely related, but beyond that the etymology is disputed. Romanians tend to claim that it is Latin in origin, typically creātiōnem ‘creation’, though there are other possibilities such as calātiōnem ‘calling’ and incarnatiōnem ‘incarnation’ (this latter one is perhaps the best semantic match; theologically Christmas is the feast of the incarnation ‘making flesh’ of God). This is plausible, but Slavicists propose a different etymology. Specifically, they contend that this form is a borrowing from a Slavic root *korčiti meaning something like ‘step forth’, from which is derived a form Kračun meaning ‘winter solstice’ (the metaphor being the sun ‘stepping forth’ after the shortest day of the year) in certain Bulgarian varieties and in Slovak, and with an attestation as Koročun in some Novgorodian manuscripts. I personally would lean towards the former, since the Slavic forms could easily be loans from the Romanian (we noted already the borrowing of calendae from Latin) and the semantic match seems something of a stretch to derive ‘winter solstice’, but we will likely never be sure.

However you celebrate (if you do), we at SMG wish you Joyeux Noël, Frohe Weinachten, Feliz Navidad, God Jul, s Rozhdestvom, and of course Merry Christmas.