On prodigal loanwords

Most people at some point in their life will have heard someone remark on how their language X (where X is any language) is getting corrupted by other languages and generally “losing its X-ness”. Today I would like to focus on one aspect of the so-called corruption of languages by other languages — lexical borrowings – and show that it’s perhaps not that bad.

European French (at least the French advertised by the Académie Française) is certainly a language about which its speakers worry, so much so that there is even an institution in charge of deciding what is French and what is not (see Helen’s earlier post). A number of English-looking/sounding words now commonly used in spoken French have indeed been taken from English, but English first took them from French!

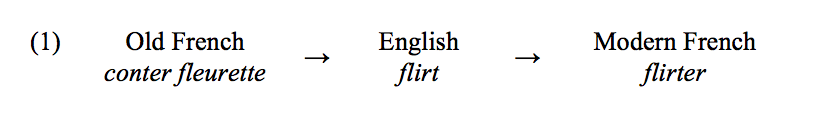

For instance, the word flirter ‘to court someone’ is obviously adapted from English to flirt and it has the same meaning in both languages. But the English word is the adaptation of the French word fleurette in the expression conter fleurette! The expression conter fleurette is no longer used (casually) in spoken French.

-

“How could the universe live without your beauty?” “I wonder how sincere he is…”

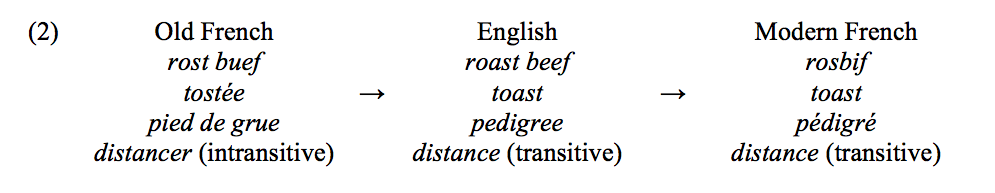

Other examples of English words borrowed from (parts of) French expressions which then get adapted into French are in (2).

Thus un rosbif is an adaptation into French of roast beef which is itself an adaptation into English of the passive participle of the verb rostir “roast” which later became rôtir in Modern French, and buef “ox/beef” which later became boeuf in the Modern French.

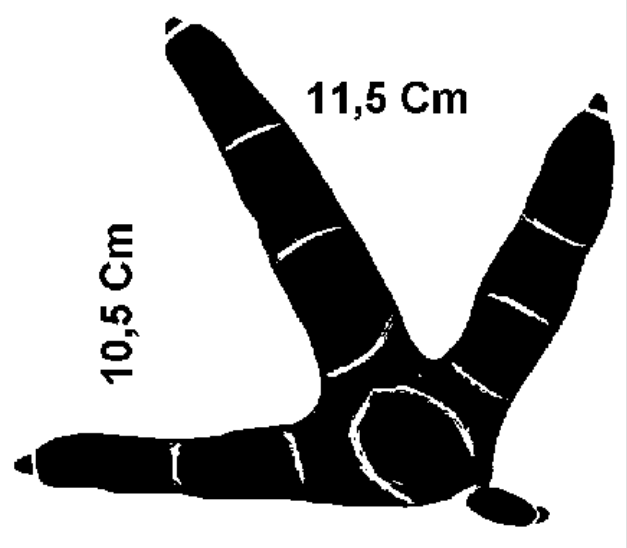

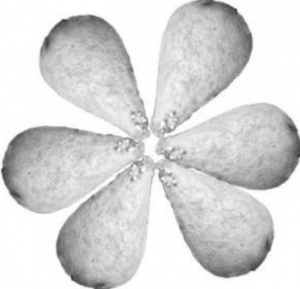

The word un toast comes from English toast with the meaning “piece of toasted bread”. The English word itself was borrowed from tostée, an Old French noun derived from the verb toster which is not used in Modern French. The word pédigré comes from English pedigree but this word is itself adapted from French pied de grue “crane foot”, describing the shape of junctions in genealogical trees.

-

Pied de grue ‘Crane foot’

Finally, the verb distancer is transitive in Modern French, which means that it requires a direct object: thus the sentence in (a) is good because the verb distancer “distance” has a direct object, the phrase la voiture blanche “the white car”. By contrast, the construction in (b) is not acceptable (signified by the * symbol) because it lacks an object.

a. La voiture rouge a distancé la voiture blanche.

‘The red car distanced the white car.’

b. *La voiture rouge a distancé.

The (transitive) Modern French verb distancer comes from English to distance which itself is a borrowing from the no-longer-used Old French verb distancer which was uniquely intransitive with the meaning “be far” (that is, in Old French, distancer could only be used in a construction with no direct object).

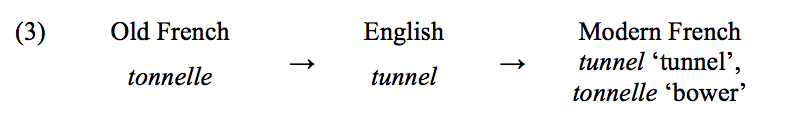

Another instance is (3): the word tonnelle ‘bower, arbor’ was borrowed into English and became tunnel under the influence of the local pronunciation. The word tunnel was then borrowed by French to refer exclusively to …. wait for it … tunnels. Both words now subsist in French with different meanings.

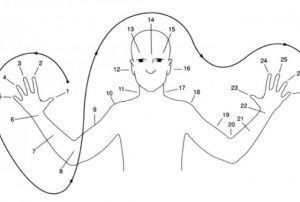

-

Une tonnelle ‘a bower’, Un tunnel ‘a tunnel’

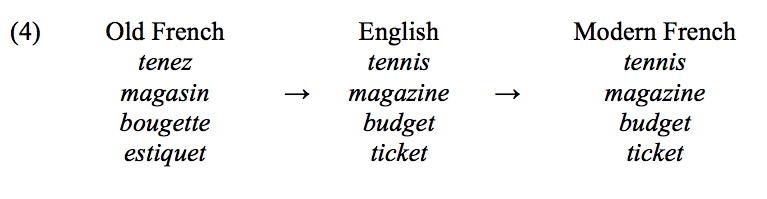

Other examples of words that were borrowed into English and ‘came back’ into French with a different meaning are in (4).

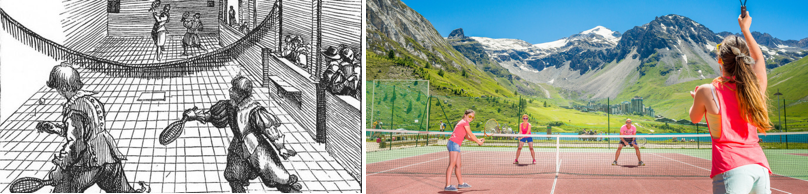

The ancestor of tennis is the jeu de paume during which players would say tenez “there you go” as they were about to serve (at that time the final “z” was pronounced [z], it is not in Modern French). This word was adapted into English and became tennis which was then borrowed back into French to refer to the sport jeu de paume evolved into.

-

Jeu de paume vs. tennis

The Middle French word magasin used to refer to a warehouse, a collection of things. This word was borrowed into English and came to refer to a collection of things on paper. The word magazine was then borrowed back into French with this new meaning.

The history of the word budget also interesting. The word bouge used to mean “bag” and a small bag was therefore bougette (the -ette suffix is used as a diminutive, e.g. fourche “pitchfork” – fourchette “fork”). The word was borrowed into English where its pronunciation was “nativized” and it came to refer to a small bag of money. It was then borrowed back into French with the new meaning of “allocated sum of money”. Finally, ticket was borrowed from English which borrowed it from French estiquet, which referred to a piece of paper where someone’s name was written.

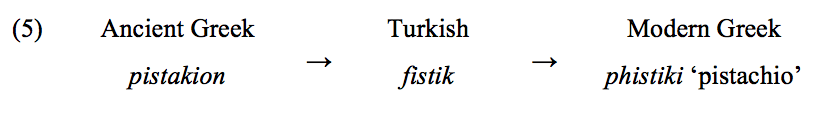

This happens in other languages of course. For instance, Turkish took the word pistakion ‘pistachio’ from (Ancient) Greek which became fistik. (Modern) Greek then borrowed this word back from Turkish which was then spelled phistiki with the meaning ‘pistachio’.

The main lesson I draw from the existence of ‘prodigal loanwords’ is that one’s impressions of language corruption often lack the perspective to actually ground that impression in reality. A French speaker looking at flirter ‘flirt’ may think that this is another sign of the influence of English — and they would be right — without being aware that this is after all a French word fleurette just coming back home.

Do you know other examples of prodigal loanwords? Please, share by commenting on this post!

Sources:

L’aventure des langues en Occident, Henriette Walter

Honni soit qui mal y pense, Henriette Walter

Jérôme Serme. 1998. Un exemple de résistance à l’innovation lexicale: les “archaïsmes” du français régional, Thèse Lyon II

Javier Herráez Pindado. 2009. Les emprunts aller-retour entre le français et l’anglais dans le sport. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

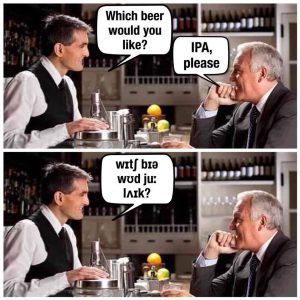

Pairs of words like file and feel, or wide and weed, have identical consonants, differing purely in their vowels. They are also spelled differently: file and wide are written with <i…e>, while feel and weed are written with <ee>. The tricky part comes when you want to tell another person in writing how these words are pronounced. To do that one normally makes a comparison with other familiar words – for example, you could tell them ‘feel rhymes with meal’ – but what do you do if the other person doesn’t speak English? In order to solve this problem, linguists in the late 19th century invented a special alphabet called the ‘International Phonetic Alphabet’ or ‘IPA’, in which each character corresponds to a single sound, and every possible sound is represented by a unique character. The idea was that this could function as a universal spelling system that anyone could use to record and communicate the sounds of different languages without any ambiguity or confusion. For file and wide, the Oxford English Dictionary website now gives two transcriptions in IPA, one in a standardised British and the other in standardised American: Brit.

Pairs of words like file and feel, or wide and weed, have identical consonants, differing purely in their vowels. They are also spelled differently: file and wide are written with <i…e>, while feel and weed are written with <ee>. The tricky part comes when you want to tell another person in writing how these words are pronounced. To do that one normally makes a comparison with other familiar words – for example, you could tell them ‘feel rhymes with meal’ – but what do you do if the other person doesn’t speak English? In order to solve this problem, linguists in the late 19th century invented a special alphabet called the ‘International Phonetic Alphabet’ or ‘IPA’, in which each character corresponds to a single sound, and every possible sound is represented by a unique character. The idea was that this could function as a universal spelling system that anyone could use to record and communicate the sounds of different languages without any ambiguity or confusion. For file and wide, the Oxford English Dictionary website now gives two transcriptions in IPA, one in a standardised British and the other in standardised American: Brit.