Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow

How do we talk about time? This may seem a simple question with a simple answer; we are all human, surely we all experience time the same way? That may be true, but that doesn’t mean that all languages organise the time in the same way. This is arguably most apparent when it comes to talking about the days either side of the present day. We all live on earth and so therefore all experience a day-night cycle; all can understand how one day follows after another. However, the words we use to locate events in this cycle can vary wildly in their construction.

Let’s take a look at two languages, Scottish Gaelic and Sylheti, and see how their systems compare with that of English. All three of these languages belong to the same family, Indo-European, so it might be assumed that they show many similarities. And yet each still exhibits significant variation in how they talk about time.

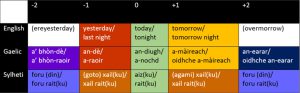

Firstly, Scottish Gaelic. Like English, it distinguishes between ‘yesterday’, ‘today’ and ‘tomorrow’. The terms each show a consistent structure with a frozen prefix a(n)- with three morphologically opaque roots; an-dè, an-diugh and a-màireach respectively. Furthermore none of the Gaelic terms has any connection with the normal word for ‘day’, latha/là. Compare English, where yester-day and to-day both feature the word ‘day’, while to-day and to-morrow both feature a frozen prefix to- (historically a demonstrative). Additionally, there are also single terms for ‘last night’ as well as ‘tonight’ with a-raoir and a-nochd respectively, again with no immediately apparent connection with the normal term for ‘night’ oidhche. On the other hand, there is no single term for ‘tomorrow night’ so the compound expression oidhche a-màireach is used instead. There are also additional terms for ‘the day after tomorrow’ and ‘the day before yesterday’, an-earar and a bhòn-dè respectively, while the latter has a counterpart in a bhòn-raoir for ‘the night before last’. English is also reported to have had similar terms in the form of ereyesterday and overmorrow, though these have fallen out of usage in the modern day.

Gaelic is also in another respect slightly more regular than English in how it refers to parts of the day. While in English we have a split between ‘this morning’ and ‘yesterday morning’, Gaelic instead uses madainn an-diugh and madainn an-dè, where the former literally translates to ‘today morning’.

But all this is not really that surprising. All that really distinguishes Scottish Gaelic from English in this respect is which time categories are given single indivisible terms rather than compositional expressions; the fundamental organisation of the system is still broadly similar to English. To see a far more radically different system of organising time words, we will now turn to Sylheti, an Indo-Aryan language spoken in north-eastern Bangladesh by around 9-10 million and by perhaps a further 1 million in diaspora, including by most of the British Bangladeshi community.

Here, instead of distinguishing between ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’, we instead find a single term xail(ku), contrasting with aiz(ku) meaning ‘today’ (the -ku is a suffix which can optionally appear on a lot of ‘time’ words, such as onku ‘now’ or bianku ‘(this) morning’). The two senses of ‘tomorrow’ and ‘yesterday’ can be distinguished by combining them with goto ‘past’ and agami ‘future’, but just as commonly instead the distinction is solely marked by whether the verb is in the past or future tense, e.g. xailku ami amar bondu dexsi ‘I saw my friend yesterday’ vs. xailku ami amar bondu dexmu ‘I will see my friend tomorrow’.

This is not an isolated instance in the language, either, but in fact represents a consistent trend. So in the same manner foru can be either ‘the day before yesterday’ or ‘the day after tomorrow’ depending on context and toʃu the same but at one day further removed.

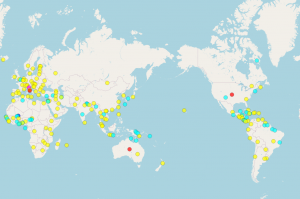

Nor is Sylheti unique in using this kind of system; it is also found in many parts of New Guinea, for example. Yimas, a language of northern New Guinea, also uses the same term ŋarŋ for both ‘yesterday’ and ‘tomorrow’, urakrŋ for ‘two days removed’ and so on, all the way up to manmaɲcŋ for ‘five days removed’. Once again whether the reference is to the past or future is carried by the choice of tense on the verb, though Yimas has a far more complex system than that seen in Sylheti, for instance distinguishing a near past -na(n) from a more remote past -ntuk~ntut.

Sylheti also has more fine grained distinctions for parts of the day than either English or Scottish Gaelic. For example, if one wishes to say ‘in the morning’ one must decide whether one is talking about the early morning (ʃoxal) or the mid to late morning (bian). Additionally, while forms such as ‘yesterday/tomorrow afternoon’, ‘the night before last/after next’ and ‘yesteray/tomorrow morning’ use compound expressions (xail madan, foru rait and xail bian/ʃoxal respextively), to express ‘this morning/this afternoon/tonight’ the word for the part of the day (perhaps with the oblique suffix -e or a time suffix -ku) is sufficient by itself, for example amra ʃoxale Sylheʈ aisi ‘We arrived in Sylhet this morning’ or ami raitku dua xotram ‘I am praying tonight’ (with rait ‘night’).

This is just one small part of the temporal vocabulary, and only looking at representatives from a single family, and yet already we see great variation in how time is organised and discussed. It is not so much that these groups have fundamentally different conceptions of time, as these languages share a common ancestor and are only separated by a few thousand years. Instead, it is a testament to the fluidity of time itself, resulting in the words used to refer to it easily shifting in meaning and being reorganised over generations.

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?

This was one of the great insights of Ferdinand de Saussure, arguably the father of modern linguistic

This was one of the great insights of Ferdinand de Saussure, arguably the father of modern linguistic