The Story of Aubergine

As the University of Surrey’s foremost (and indeed only) blog about languages and how they change, MORPH is enjoyed by literally dozens of avid readers from all over the world. But so far these multitudes have not received an answer to the one big linguistic question besetting modern society. Namely, what on earth is going on with the name of the plant that British English calls the aubergine, but that in other times and places has been called eggplant, melongene, brown-jolly, mad-apple, and so much more? Where do all these weird names come from?

I think the time has finally come to put everyone’s mind at rest. Aubergines may not seem particularly eggy, melonish, jolly or mad, but lots of the apparently diverse and whimsical terms for them used in English and other languages are actually connected – and in trying to understand how, we can get some insight about how vocabulary spreads and develops over time. It turns out that one powerful impulse behind language change is the fact that speakers like to ‘make sense’ of things that do not inherently make sense. What do I mean by that? Stay tuned to find out.

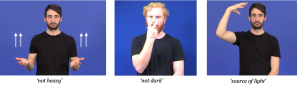

To get one not-so-linguistic point out of the way first, there is no real mystery about eggplant (the word generally used in the US and some other English-speaking countries, dating back to the 18th century), which is not linked to anything else I am talking about here. It is hard to imagine mistaking the large, purple fruit in the photo above for any kind of egg, but that is not the only kind of aubergine in existence. There are cultivars with a much more oval shape, and even ones with white rather than purple skin: pictures like this, showing an imposter alongside some real eggs, make it obvious how the word eggplant was able to catch on.

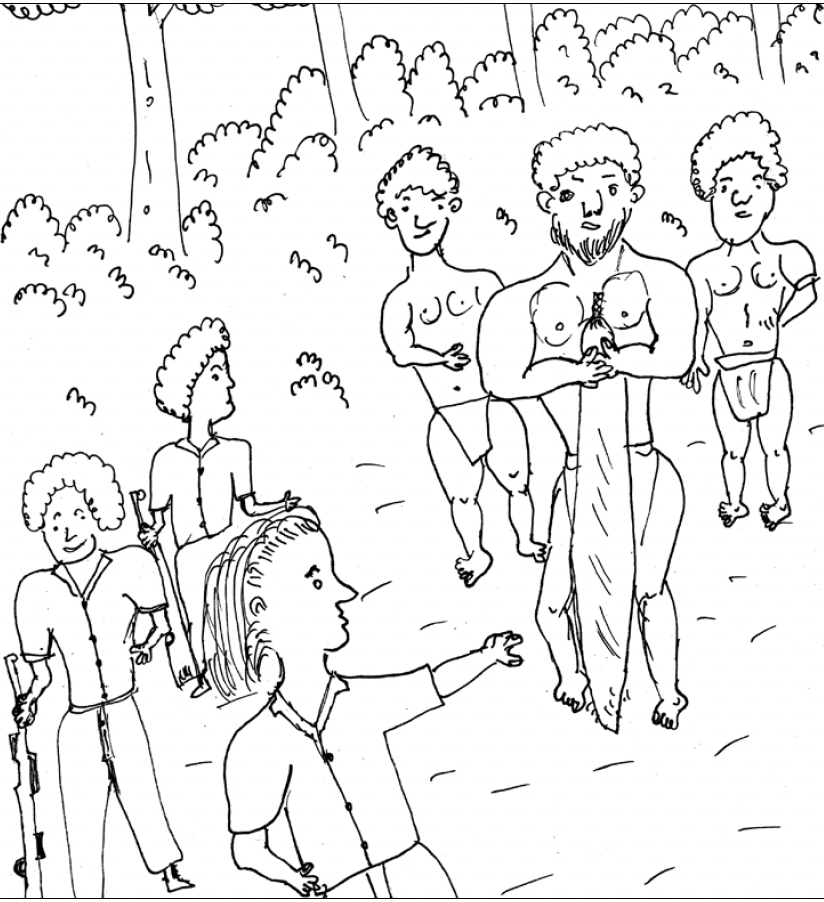

Meanwhile, aubergine, which is borrowed from French as you might expect, has a much more complex history, and can be traced back over many centuries, hopping from language to language with minor adjustments along the way. The plant is not native to the US, Britain or France, but to southern or eastern Asia, and investigating the history of the word will eventually take us back in the right geographical direction. Aubergine got into French from the Catalan albergínia, whose first syllable gives us a clue as to where we should look next: as in many al- words in the Iberian peninsula (e.g. Spanish algodón ‘cotton’), it reflects the Arabic definite article. So, along with medieval Spanish alberengena, the Catalan item is from Arabic al-bādhinjān ‘the aubergine’, where only the bādhinjān bit will be relevant from here on. This connection makes sense, because the Arab conquest had such an impact on the history of Iberia. And more generally, we have the Arabs to thank for the spread of aubergine cultivation into the West, and also – indirectly – for this charming illustration in a 14th-century Latin translation of an Arabic health manual:

But bādhinjān is not Arabic in origin either: it was borrowed into Arabic from its neighbour, Persian. In turn, Persian bādenjān is a borrowing from Sanskrit vātiṅgaṇa… and Sanskrit itself got this from some other language of India, probably belonging to the unrelated Dravidian family. The word for aubergine in Tamil, vaṟutuṇai, is an example of how the word developed inside Dravidian itself.

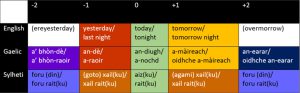

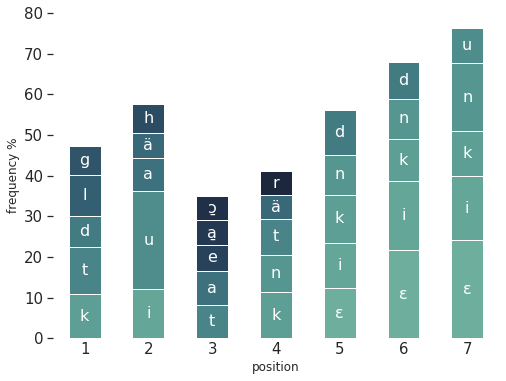

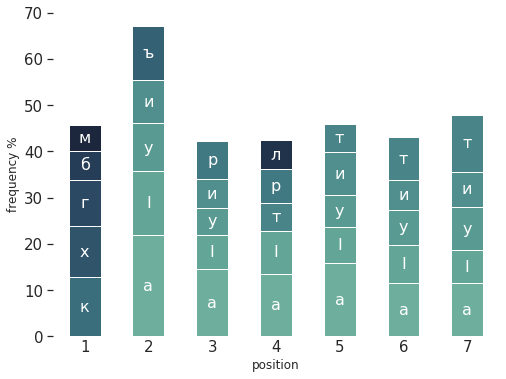

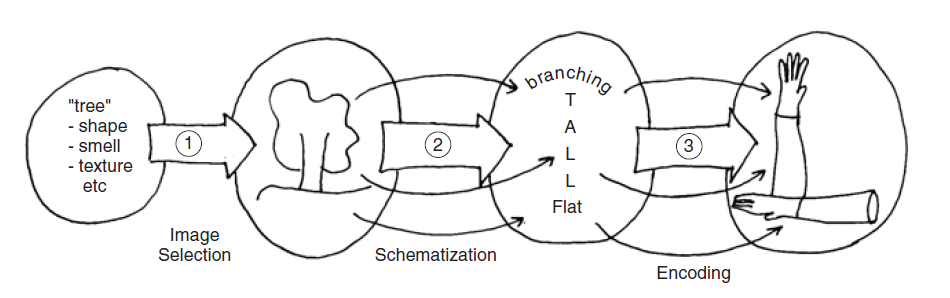

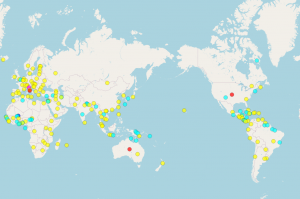

That is as far back as we are able to trace the word. But the journey has already been quite convoluted. To recap, a Dravidian item was borrowed into Sanskrit, from there into Persian, from there into Arabic, from there into Catalan, from there into French, and from there into English – and in the course of that process, it managed to go from something along the lines of vaṟutuṇai to the very different aubergine, although the individual changes were not drastic at any stage. The whole thing illustrates how developments in language can go with cultural change, in that words sometimes spread together with the things they refer to. In the same way, tea reached Europe via two routes originating in different Chinese dialect zones, and that is what gave rise to the split between ‘tea’-type and ‘chai’-type words in European languages:

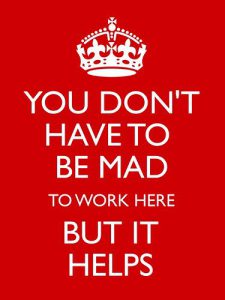

Meanwhile the word turns up in medieval Latin as melongena (giving the antiquated English melongene) and in Italian as melanzana, and a similar thing happened: here mel- has nothing to do with the dark colour of the fruit, but it did remind speakers of the word for ‘apple’, mela. We know this because melanzana was subsequently reinterpreted as the expression mela insana, ‘insane apple’. To produce this interpretation, it must have helped that the aubergine (like the equally suspicious tomato) belongs to the ‘deadly’ nightshade family, whose traditional European representatives are famously toxic. So, again, something that was originally just a word, with no deeper meaning inside, was reimagined so that it ‘made sense’. As a direct translation, English started calling the aubergine a mad-apple in the 1500s.

There are many more developments we could trace. For example, I have not talked at all about the branch of this aubergine ‘tree’ that entered the Ottoman Empire and from there spread widely across Europe and Asia. But instead I will return now to the Arab conquest of Iberia. This brought bādhinjān into Portuguese in the form beringela, and then when the Portuguese started making conquests of their own, versions of beringela appeared around the world. Notably, briñjal was borrowed into Gujarati and brinjal into Indian English, meaning that something-like-vaṟutuṇai ultimately came full circle, returning in this heavy disguise to its ancestral home of India. And to end on a particularly happy note, when the same form brinjal reached the Caribbean, English speakers there saw their own opportunity to ‘make sense’ of it – this time by adapting it into brown-jolly.

Brown-jolly is pretty close to the mark in terms of colour, and it is much better marketing than mela insana. But from the linguist’s point of view, they both reinforce a point which has often been made: speakers are always alive to the possibility that the expressions they use are not just arbitrary, but can be analysed, even if that means coming up with new meanings which were not originally there. To illustrate the power of ‘folk etymology’ of this kind, linguists traditionally turn to the word asparagus, reinterpreted in some varieties of English as sparrow-grass. But perhaps it is time for us to give the brown-jolly its moment in the sun.