A Rainbow of Shared Diversity: Culture and Language in the South Pacific

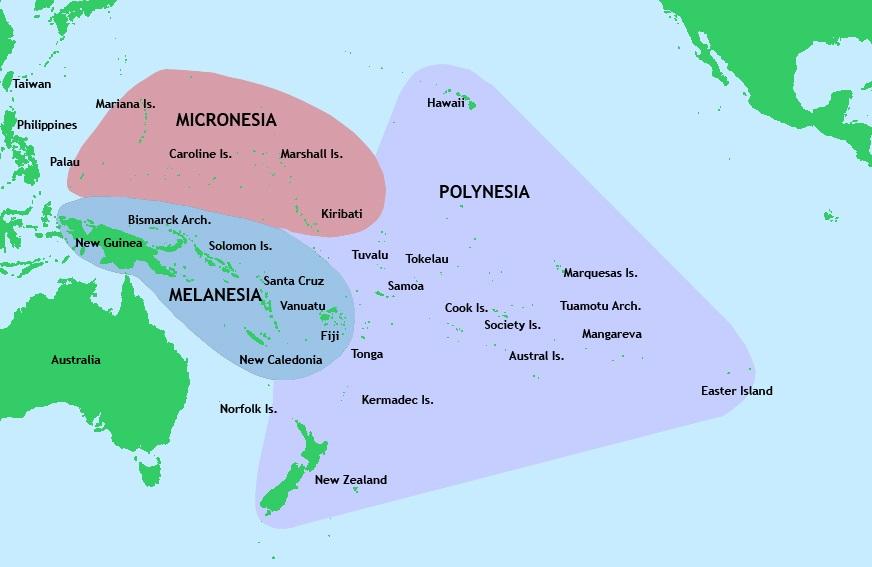

When we think of life in the South Pacific we often imagine relaxing in the shade of a coconut palm listening to the soothing sound of Israel Kamakawiwoʻole’s ‘over the rainbow’ (the official song of this blog post and mandatory listening!). But the South Pacific is in fact culturally diverse, and linguistically too, with around 600 languages in the Oceanic family spread across Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia.

The original migration of the Oceanic speaking people started around 1600 BC from the north east of New Guinea and they went on to colonise the uninhabited islands of the Pacific Ocean, with New Zealand being the last country to be inhabited by Polynesian seafarers as late as 1285 CE. The vast distances have created huge cultural differences amongst contemporary Oceanic peoples, yet they all speak languages that stem from Proto-Oceanic – the ancestral language of all of Oceania. For example, the Polynesians are famed for their ability to cross vast swathes of Ocean by using star charts made out of sticks, whereas the Melanesians were not great seafarers. However all Oceanic peoples share similar horticultural practices of cultivating yam and taro root crops, which form the basis of an Oceanic diet.

The enormous cultural diversity amongst the Oceanic speaking people has led to widespread variation in the languages spoken in the South Pacific. In particular we can see the cultural influence on the various languages in how they encode possessive relationships in the language. In the most basic way, an Oceanic language makes a difference in the way it treats alienable and inalienable possessions. We’re not talking UFOs here! Inalienable possessions are those that have an inherent connection with the person to whom they belong – such as body parts or members of the family. Alienable possessions are items that can easily be transferred from one owner to another, such as food, baskets, or other household items.

In Port Sandwich, a language spoken in Vanuatu, possessions that are considered inalienable often have a suffix that encodes the possessor (my, your, his/her) directly attached to the possessed noun

(1) naru-ngg

son-my

‘my son’

Whereas when speaking about sandwiches (and all other alienable possessions) in Port Sandwich, encoding is indirect. The possessor suffix is not able to attach directly to the possessed noun, but instead must attach to a separate marker of possession:

(2) sanwis isa-ngg

sandwich POSS.MARKER-my

‘my sandwich’

Sandwiches aside, in many Oceanic languages this indirect construction that is used for alienable possessions has expanded to include various different semantic types of possession. Languages have separate possessive markers, often called classifiers. Many languages have a three-way split, such as in the language Wuvulu (spoken in the Western Islands off the north coast of Papua New Guinea), for possessions that are eaten, drunk or everything else:

3a. ana-u niu b. numa-mu upu c. ape-muponata

FOOD-my fish. DRINK-your coconut GENERAL-your dog

‘my fish (to eat)’ ‘your coconut (to drink)’ ‘your dog (as a pet)’

Some languages make even more semantic distinctions between alienable items. These classifiers often encode culturally important semantic distinctions. Vera’a, spoken in northern Vanuatu, has eight different possessive classifiers: food, drinks, canoes, houses, beds and mats, prized possessions, long-term possessions, and one for everything else. The Micronesian languages have the largest inventory of classifiers in Oceanic. The Chuuk language has developed thirty-five distinct classifiers, yes, thirty-five! Several of which are used to categorise different types of edible possessions. For example, there is a classifier for cooked food, one for raw food, one for leftover food, and even one that is used with food taken on a journey – great for classifying take-away food!

In other languages, speakers are able to create new classifiers when they need to on an ad-hoc basis. This mechanism is particularly prevalent in the languages of Micronesia and New Caledonia. Nêlêmwa, spoken in New Caledonia, can create new classifiers by repeating the possessed noun and adding a suffix to show the possessor, for example mwa ‘house’ (4a) can have the possessor suffix attached (4b), but if a speaker adds an adjective then the possessed noun must be repeated and the directly possessed noun functions as a classifier (4c). In this way a speaker of Nêlêmwa can create new classifiers whenever the need arises.

4a. mwa b. mwa-n c. mwa-n mwa doo

house house-his house-his house earth

house ‘his house’ ‘his earth-house’

Though cultural diversity plays a role in the formation of classifiers that are unique to particular languages in the Pacific, there is a commonality among classifiers, and languages that are located far apart often have classifiers that encode similar semantics, which means that though culturally diverse, some important cultural aspects are shared across the Oceanic peoples. For example, many of the Micronesian languages have developed classifiers for beds, mats and pillows. But the language of Vera’a spoken in Northern Vanuatu (over 2500 kilometers away) has also developed a classifier for sleep-related possessions. Similarly, classifiers for domesticated animals have developed in the languages of Micronesia, in Mussau and Seimat (both spoken on the offshore islands of Papua New Guinea), and in Nêlêmwa and Iaai, spoken in New Caledonia. The words used for these classifiers can’t be traced back to a single historical root, which means that these are sporadic innovations in these languages and point to the shared cultural life of the Oceanic peoples.

Just as speakers of different languages can name varying numbers of colours in a rainbow, with Israel Kamakawiwoʻole’s mother tongue Hawaiian distinguishing six colours in contrast to English’s seven, speakers of Oceanic languages differ in the number of ways of categorising their possessions.

One thought on “A Rainbow of Shared Diversity: Culture and Language in the South Pacific”