Whisky Galore and A Go Go!

When it comes to etymology, most words have a somewhat mundane route into a language: they either are retained from a direct ancestor or were borrowed at some point from another language. Within the latter category, these words tend to come in batches, often either through an intensive period of contact between peoples, as with the Old Norse loans into English, or through the importation of specific vocabulary which related to aspects of culture which were being borrowed from the group in question, such as e.g law terms deriving from the French used in English courts after the Norman Conquest.

However, every so often, there come along lexical items with a significantly more complex and idiosyncratic path into a language, and occasionally words may interplay with one another in interesting ways. We find such a complex interplay with galore and agogo.

Galore by itself is already an interesting form, as it is one of a small number of loanwords from Gaelic (likely specifically Scottish gu leòr) which does not have some kind of connection with Gaelic culture or geography. This expression can mean either ‘enough’ or ‘much, plenty’, and occurs in several constructions as a result. For instance, in Scottish Gaelic when asked ‘how are you?’, one might respond ceart gu leòr ‘all right, OK’, literally ‘right enough’.

This phrase, in a number of varying spellings such as gilore or gallore, appears to have begun to arrive in English in the mid 17th Century (or at least this is the date of the earliest citation in the Oxford English Dictionary). When this form was borrowed into English it underwent semantic shift and narrowing, coming to specifically mean ‘in abundance, plenty’, losing the sense of ‘enough’. It seems to have been somewhat colloquial in use, not being particularly frequent in writing, and is disproportionately concentrated in Scottish works, including an attestation in the journals of Walter Scott.

This form comes to its greatest in prominence in English through its use in a Compton Mackenzie novel and later Ealing comedy titled Whisky Galore! Both the novel and film centre on a remote Scottish island, and the novel in particular makes use of Gaelic throughout, so the use of ‘galore’ fits in well with the setting.

This work in particular, however, had a more interesting impact than simple popularity. As with many best-selling works, it received translations into other languages, and in this case the French translation was titled Whisky à-Gogo, deriving likely from the Old French gogue ‘fun’. This title then was itself used as the name of a nightclub in Paris, the world’s first discothèque. The concept rapidly grew in popularity, with Whisky à-Gogo venues spreading across the globe, as far as Papeete in Tahiti (and Cardiff!), the most famous probably being the the Whisky a Go Go on Sunset Strip in Hollywood. (In the English-speaking world gogo got split into two, possibly on false analogy with the verb ‘go’.)

From here on ‘a go go’ or just ‘go go’ became a by-word for everything hip and cool (or ‘groovy’) in the 1960s. Go-go dancers dance in go-go clubs, of course, but the meaning became more and more nebulous over time. In cinema, 1965 was a banner year, with Roadrunner a go-go up against Monster a go-go. This year also an unsuccessful attempt to extend this—word? phrase?—by analogy, with the notorious Batman parody Rat Pfink a Boo Boo. Nobody seems to have got this (not terribly good) joke, and on subsequent reissues the film was “corrected” to Rat Pfink and Boo Boo. (You’re reading this etymology here first. Even the director who came up with the title didn’t realize it, but we’re linguists, we know better.) But the shelf life of terms denoting popular trends is short, and anyone using it now probably means for it to lend antiquated flavour of the swinging 60s. Contrast with galore, which retains its more generic use and seems unlikely to drop out of common usage in the near future.

Here I make my own foray into speculation; you read it here first. Poland is not just a land of sourdough rye bread, it is a land of a

Here I make my own foray into speculation; you read it here first. Poland is not just a land of sourdough rye bread, it is a land of a  Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well.

Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well. James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew:

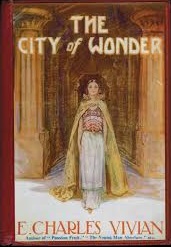

James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew: Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions:

Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions: Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where

Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)

Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)