Werewolves

Hallowe’en will soon be upon us, so it is only right we turn our attention to monsters. Consider the werewolf. It’s a wolf, sort of, as the name indicates, but what’s a were? The usual assumption is that it’s a leftover of an older word meaning ‘man’ that fell completely out of fashion by the 14th century. As a result we have what looks like a compound word, except that one of the parts doesn’t have any meaning on its own. Perhaps not, but that hasn’t stopped people from squeezing some value out of it nonetheless: if a werewolf is a person who turns into a wolf — or at any rate, part person, part wolf — then a were-bear is a mixture of person and bear, and so on down to were-turtles.

Actually, people don’t seem to be that literal-minded when it comes to word meanings, if the various were-creatures in circulation are any evidence. The monster from “Wallace and Gromit: Curse of the Were-Rabbit” is not half-human, half-rabbit, but more just kind of a monster rabbit, with a thicker pelt. (Visually calqued, I suspect, from the not-particularly wolf-like wolfman of the wolfman movies featuring Lon Chaney Jr.)

And were-fleas, to the extent that they exist, appear to be carriers of lycanthropism rather than human/insect conglomerates. None of this is yet reflected in the Oxford English Dictionary’s entry on were– (you need a subscription for that but it’s free if you have a UK public library card!). Give it a few decades more maybe.

Strangely, words for werewolf in other languages share a propensity for being compounds made up of ‘wolf’ plus some other completely opaque element. The first part of Czech vlkodlak is vlk, which means ‘wolf‘, but dlak on its own is not an independent word. (Not in Czech at any rate, but in the related language Slovenian the equivalent word volkodlak is clearly made up of volk ‘wolf’ and dlaka, which means ‘hair’ or ‘fur’.) And the French werewolf, loup-garou, has the word for ‘wolf’ in it (loup), but garou is not an independent word (other than being an unrelated homonym meaning ‘flax-leaved daphne’). That part seems to have been our very own Germanic word werewolf borrowed at an early date (earliest attestation as garwall from the 12th century). Both of these have, like werewolf, given rise to further monstrous hybrids like Czech prasodlak, from prase ‘pig’, or the French cochon-garou.

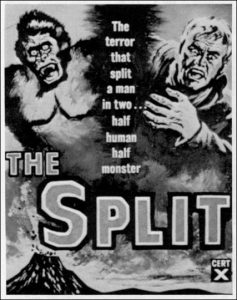

In fact, Czech and French have gone one step further than English. Though I just wrote that dlak and garou were not words, that was being a bit pedantic. Neither of them are listed in the authoritative Academy dictionaries of Czech and French, but nonetheless they do seem to have split off from their host body, rather as happened — if we can be permitted to mix monster metaphors — to the hero of 1959’s “The Manster (a.k.a The Split)”.

For example, this Czech website tells us about vlkodlaci i jiní dlaci ‘werewolves and other were-creatures’ (dlaci is the plural of dlak), and in French the phrase courir le garou ‘run the garou‘ used, at least, to be in circulation, meaning basically ‘go around at night being a werewolf”. That use in turn apparently spawned a verb garouter, meaning much the same thing. The curse lives on.