Of the saintly and sinister: words for the left-handed

A couple of years ago, when I was still living in North Yorkshire but shortly to be moving further south, I attended a function at one of the final services conducted by my mother (an ordained priest in the Church of England) in a rural parish church. Afterwards, over a goodly spread of finger-food (what in clerical circles is commonly referred to as a bun-fight), I was in conversation with one of my mother’s then parishioners, a local farmer, who was much interested in my studies in linguistics. He tasked me with sourcing the etymology of an unusual local term – cuddy-wifter, which I was told refers to a left-handed person. I’ll propose an etymology of this specific term later, but first let’s have a short discussion of terms for “left hand” across languages.

Firstly, it is important to note that many languages do not really make use of such ego-centric terms as “left” or “right” much, if at all. In these languages instead speakers opt for a geocentric system, locating and orienting objects and themselves by their relationship to either the points of the compass or in some cases the landscape. This has been most famously documented in a number of Paman languages of Queensland, Australia. For example, a speaker of Guugu Yimidhirr might refer to their nagaalngurr “east side” or guwaalngurr “west side” rather than to their left or right. Aspects of this conception of space are also found widely in languages across the Pacific and beyond.

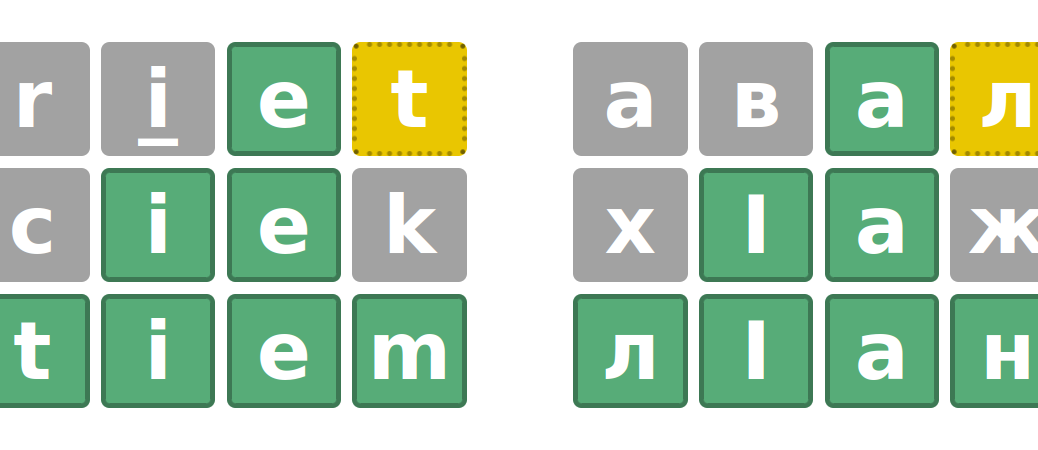

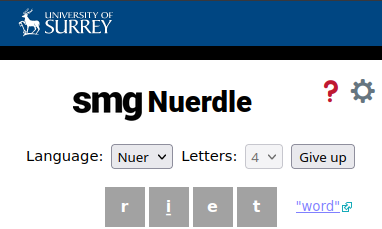

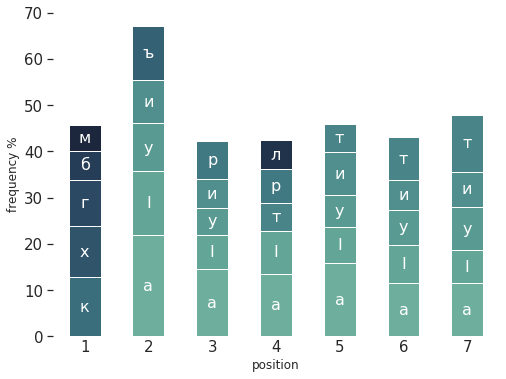

And where languages do have a term for “left”, they very frequently differ on what the term should be. Even only looking at the Indo-European family we find a multiplicity of terms: besides English left we find forms as clì or ceàrr in Scottish Gaelic; izquierdo in Spanish; majtë in Albanian; levyj in Russian; chap in Persian: and bau in Sylheti. So many different words, and these languages are all related!

From whence then English left? We can find cognates in nearby parts of West Germanic, such as West Frisian lafter/lofter and Dutch lucht/luft, but none further afield meaning “left”. These forms derive ultimately from a term meaning “palsy, paralysis”, which might perhaps derive from a Proto-Indo-European verb *lewp- “peel, break” which would also through another derivation gives the English verb lop. A similar pattern appears to hold in closely related German links which, though it doesn’t appear directly related and is of somewhat unclear etymology, the Icelandic form linur meaning “weak, feeble” indicates likely a similar semantic development.

On the other end of the scale, terms for the left hand or left-handedness can often end up taking on other meanings. Notably, this has happened twice in English borrowing from two different Romance languages, Latin and French. In the case of the Latin term sinister, it now refers to someone or something that is seen as being shadowing and potentially malicious. In the case of the French term gauche (ultimately derived from the same root as English walk), it instead refers to a lack of fashionability and perhaps a degree of awkwardness.

We can therefore draw two main conclusions from the above. Firstly, the concepts “left” and “right” are not essential to how we as humans conceptualise ourselves and the wider world; many languages do without, and those which have words for them seem to be happy to churn out old forms for new ones (compare e.g. the near-universal agreement on a form deriving from something like *mātēr for “mother” in the various Indo-European languages mentioned above). Secondly, there is a clear tendency for the left hand to carry a negative connotation, either directly due to being the non-dominant hand for most people (as indicated by the various etymologies referring to physical weakness in Germanic) or through some more cultural taboos (as seen by the development of the Romance terms sinister and gauche in English).

What then of cuddy-wifter? Well, the exact origin is not given specifically in any source I could find, but with a bit of digging uncovers the following. The “wifter” part is easier to pin down, as at least according to the Oxford English Dictionary (the pre-eminent source on English etymology) “wift” comes up sometime in the 16th century as a verb meaning something like “to turn aside” or “to drift”, which, going by the pattern set by the above data, seems a reasonable source (at least in part) for a term for “left hand”.

The cuddy part is the more problematic element. Cuddy is an affectionate form of Cuthbert, the pre-eminent saint of the North-East of England, and crops up in a number of terms from the region, notably cuddy ducks to refer to the eider ducks said to have been particularly beloved by the saint, as well as the ponies used in the many coal mines of the area, which were referred to simply as cuddies. However, the connection with the saint seems suspect from the off, as there doesn’t appear to be any kind of source which would attest to the saint being left-handed. Certainly, the Venerable Bede, that great chronicler of Anglo-Saxon England, makes no mention of anything of the kind, in contrast to his willingness to comment on much else of the saint’s physical characteristics.

There also exists a sense of “cuddy” meaning “a stupid fellow” which perhaps would tie into the negativity often associated with left-handedness. However, the OED only provides examples from the mid-nineteenth century and appears to derive from the “pony” usage (in a similar manner to the development of ass more broadly in English), which does somewhat problematise this as an etymology. In particular, the structure of cuddy-wifter this would require seems oddly-formed, akin to something like ass-drifter, and the timespan of a century for this form to arise and spread south of the Tees, well outside the coalfield regions where the pit-pony was a fact of life, is probably a bit of a stretch.

Perhaps then we should look elsewhere for a source. Old English appears to provide no obvious sources, so perhaps we should look to Celtic for an origin. And a tantalising hint we find: Welsh chwith “left” or “wrong” and Irish and Scottish Gaelic ciotach “left-handed” or “clumsy” (there’s that negativity again), pointing to a Proto-Celtic *skittos, which to my mind looks like it might have a relationship at some point with English skew, though that is far from proven at this stage. I would propose, then, that this word was borrowed into a northern variety of English (perhaps from Cumbric, the extinct Celtic language of Cumbria) as something like *cwithy~*cuthy, and then later on it was folded into the cuddy form, with no actual direct connection with the saint at all.

So, while admittedly I haven’t been able to come up with a definite answer to that question I was set at that bun-fight a couple of years ago, I can at least tell a story rich in history and culture, revealing much both of the linguistic landscape of Britain and of our historic attitudes towards those who are left-handed.