A narrow hope has fallen man, till Volapük shall reign

WHEN the tower of Babel looked up toward the sky.

Before the huge walls were complete,

They knew but one language, to which we apply,

The musical name “Volapuk.”But a slight little trouble occurring one day,

They had to stop work, so to speak,

And drop all their tools and hurry away,

Because they forgot “Volapuk.”And from that day to this men have been on the search.

For that long lost Volapuk

(Louis Eisenbeis, author of Come, swell the ranks of temperance)

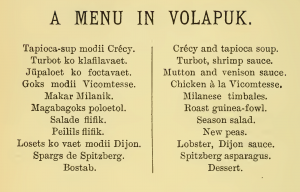

Volapük may well have had the shortest lifespan of any known language, at least one that has had dictionaries and grammars devoted to it. It was the first serious attempt at an artificial ‘universal’ language. Devised in the 1880s by the German priest Johann Schleyer, it rapidly soared in popularity, attracting passionate followers the world over, but by the end of the century it was already being pronounced a dead language. Many factors probably led to its demise, not the least of which is that an artificial language is not a very good idea in the first place. And as artificial languages go, Volapük was as complicated as it was peculiar, nor could anyone ever even seem to agree on how it should be pronounced.

But although Volapük never really got off the ground in the real world, it did enjoy a shadowy life in fiction and as an object of idle speculation. So I offer here a virtual history of Volapük in a world that might have been, where we can sing with the poet: A narrow hope has fallen man, till Volapük shall reign.

The language enjoys a robust future in Alvarado Fuller’s 1890 novel A.D. 2000. The main character is put in suspended animation by means of an ‘ozone machine’, and wakes up in (wait for it…) the year 2000, where he puts his knowledge of Volapük to good use, since it has become the common language of ‘civilized nations’.

A practical step in that direction was proposed in Oskar Kausch’s monumental Die Sprachwissenschaft in der Briefmarkenkunde ‘Linguistics in Philately’ (1894), an exhaustive study of the linguistic aspects of stamp collecting. Kausch moots the use of Volapük in international address labels. Didn’t happen.

Looking at things from the other perspective, the futuristic satire El clavo ‘The Nail’ (1967) by the artist and author Eugenio Granell imagines Volapük as a language spoken in some tribal past, which may be an alternative reality to our present (or past or future for that matter?).

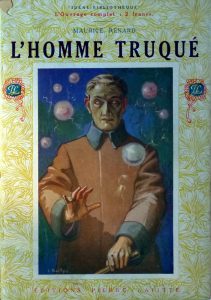

In Maurice Renard’s gruesome and sardonic L’homme truqué ‘The Counterfeit Man’ (1921), Volapük has been taken up as the language of mad scientists. A French soldier in WWI is blinded in battle, captured by the Germans but then shipped off to a castle somewhere in Eastern Europe where a mysterious group of Volapük-speaking scientists are performing ghastly experiments on human subjects. (Highly recommended.)

Extraterrestrials got into the act as well. In James Cowan’s Daybreak (1896), Moon dwellers fire off bombs to Earth filled, among other things, with Volapük texts, thereby successfully introducing the language. This conflicts somewhat with a report from an Illinois newspaper the following year, in which a Close Encounter of the Third kind was reported with a Volapük-speaking member of a Martian expeditionary force.

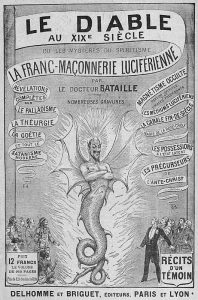

In the end, as always, it is Satan’s triumph. Or so reports a certain pseudonymous Doctor Bataille in Le Diable au XIX Siècle (1895). Sadly I have not been able to source the original, but as paraphrased in the following year by Arthur Edward Waite in Devil-Worship in France, he reports having discovered that the English had excavated caverns in Gibraltar to house workshops for the manufacture of Satanic idols. These are staffed by English convicts who

commonly communicate with each other in the language of Volapuk. The reason given is that this language has been adopted by the Spoeleic Rite, which I confess that I had not heard of previously, but I venture to think that the doctor has concealed the true reason, and that Volapuk has been thus chosen because it is a diabolical invention ; a universal language prevailed previously to the confusion of Babel, and the new language is an irreligious attempt to produce ordo ab chao by a return to unity of speech.