Remember, remember

A lot of the work that linguists do involves taking a language as it is spoken at a particular time, finding generalizations about how it operates, and coming up with abstractions to make sense of them. In English, for example, we identify a category of ‘number’ (with possible values ‘singular’ and ‘plural’); and we do that because in many ways the relationship between cat and cats is the same as that between mouse and mice, man and men, and so on, meaning that it would be useful to treat all of these pairings as specific examples of a more general phenomenon. We can then make the further generalization that whatever this linguistic concept of ‘number’ really is, it is not only relevant to nouns but also to verbs, and to some other items too – because English speakers all know that this cat scratches whereas these cats scratch, and you can’t have any other combination like *these cat scratch.

Once you start looking, you discover layer upon layer of generalizations like these, and you need more and more abstractions in order to take care of them all. This all gives rise to a view of language as a kind of machine built out of abstract principles, all coexisting at the same time inside a speaker’s head. On that basis, we can ask questions like: are there any principles that all languages use? Does having pattern X always go along with having pattern Y? Are there any generalizations that you can easily come up with, but that turn out not to be found anywhere? What does all this tell us about human psychology?

But that is not the only approach to language we could take. While we can point to a general principle of English to explain what is wrong with these cat, there is no similar principle explaining why we refer to the meowing, purring, scratching creature as a cat in the first place. The word cat has nothing feline about it, and the fact that we use that sequence of sounds – rather than e.g. tac – is not based on some higher-level truth that applies for all English speakers right now: instead, the ‘explanation’ is rooted in the fact that this is the word we happened to inherit from earlier generations of speakers.

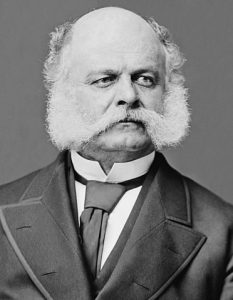

So studying the etymology of individual words serves as a good reminder that as well as an abstract, principled system residing in human minds, every language is also a contingent historical artefact, shaped by the peoples and cultures of the past.1 Nothing makes this more obvious than the continued existence of ordinary vocabulary items that commemorate individuals from centuries gone by – often without modern-day speakers even knowing it. In English, sandwiches are named after the Earl of Sandwich, wellingtons are named after the Duke of Wellington, and cardigans are named after the Earl of Cardigan; and the parallelism here says something about the locus of cultural influence in Georgian and Victorian Britain. More cryptically, sideburns owe their name to a General Burnside of the US Army, justly famed for his facial hair; algorithms celebrate the Persian mathematician al-Khwarizmi; and Duns Scotus, although a towering figure of medieval philosophy, now lives on in the word dunce popularized by his academic opponents.2

But which historical figure has had the greatest success of all in getting his name woven into the fabric of modern English? I reckon that, against all the odds, it could well be this Guy.

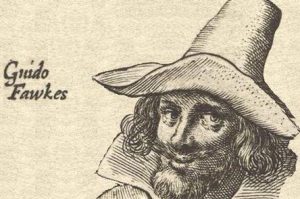

While all English speakers are familiar with the word guy as an informal word corresponding to man, probably not that many know that it can be traced back to a historical figure from 400 years ago who, in a modern context, would be called a religious terrorist. Guy Fawkes was one of the conspirators in the ‘Gunpowder Plot’ of November 1605: with the aim of installing a Catholic monarchy, they planned to assassinate England’s Protestant king, James I, by blowing up Parliament with him inside. Fawkes was not one of the leaders of the conspiracy, but he was the one caught red-handed with the gunpowder; as a result, one cultural legacy of the plot’s failure is the celebration every 5th November (principally in the UK) of Guy Fawkes Night, which commonly involves letting off fireworks and setting a bonfire on which a crude effigy of Fawkes was traditionally burnt.

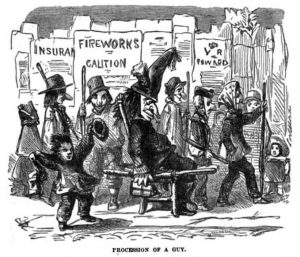

But how did the name of one specific Guy, for a while the most detested man in the English-speaking world, end up becoming a ubiquitous informal term applying to any man? The crucial factor is the effigy. It is unsurprising that this came to be called a Guy, ‘in honour’ of the man himself; but by the 19th century, the word was also being used to refer to actual men who dressed badly enough to earn the same label, in the way one might jokingly liken someone to a scarecrow (one British woman writing home from Madras in 1836 commented: ‘The gentlemen are all ‘rigged Tropical’,… grisly Guys some of them turn out!’). It is not a big step from there to using guy as a humorous and, eventually, just a colloquial word for men in general.3

And of course the story does not stop there. While a guy is still almost always a man, for many speakers the plural guys can now refer to people in general, especially as a term of address. The idea that a word with such unambiguously masculine origins could ever be treated as gender-neutral has been something of a talking point in recent years, as in this article from The Atlantic about the rights and wrongs of greeting women with a friendly ‘hey guys’; but the fact that it is debated at all shows that it is happening. In fact, there is good reason to think that in some varieties of English, you-guys is being adopted as a plural form of the personal pronoun you: one piece of evidence is the existence of special possessive forms like your-guys’s, a distinctively plural version of your.

It is interesting to notice that the rise of non-standard you-guys, not unlike y’all and youse, goes some way towards ‘fixing’ an anomaly within modern English as a system: almost all nouns, and all other personal pronouns, have distinct singular and plural forms, whereas the standard language currently has the same form you doing double duty as both singular and plural. Any one of these plural versions of you might eventually win out, further strengthening the (already pretty reliable) generalization that English singulars and plurals are formally distinct. This just goes to show that the two ways of looking at language – as a synchronic system, and as a historical object – need to complement each other if we really want to understand what is going on. At the same time, it is fun to think of linguists of the distant future researching the poorly attested Ancient English language of the twenty-second century, and wondering where the mysterious personal pronoun yugaiz came from. Would anyone who didn’t know the facts dare to suggest that the second syllable of this gender-neutral plural pronoun came from the given name of a singular male criminal, executed many centuries before?

- For example, cat itself seems to be traceable back to an ancient language of North Africa, reflecting the fact that cats were household animals among the Egyptians for millennia before they became popular mousers in Europe. [↩]

- Of course, it is no accident that all of these examples feature men. Relatively few women in history have had the opportunity to turn into items of English vocabulary; in fact, fictional female characters – largely from classical mythology – have had much greater success, giving us e.g. calypso, rhea and Europe. [↩]

- A similar thing also happened to the word joker in the 19th century, though it didn’t get as far as guy: that suggests that sentences containing guy would once have had the same ring to them as Who’s this joker?; and then some joker turns up and says… [↩]

One thought on “Remember, remember”

The use of ‘guy’ is not restricted to ‘man’. It’s not uncommon for my wife and me to be addressed informally as ‘guys’. I have to admit I’m not thrilled!