Making cuts in the wrong places

When you want to look up a word, how do you go about it? The dictionary is organised by the first letter of the word, so that is what you consider first. And when you want to compare languages, what is the first thing to catch your eye? Again, the first sound. Thus, when looking at a set of words like English fish, father, full, Latin piscis, pater, plenus and Scottish Gaelic iasg, athair, làn, the fact that f- in English corresponds to p- in Latin and zero in Scottish Gaelic spring immediately to our attention, reading as we do from left to right.

Thus, we might presume that the beginning of a word is somehow especially stable, and that sounds which appear at the beginning of a word are a good first indicator of etymology. However, in fact the beginning of a word is not so immutable as you might suppose. Famously, Celtic languages have initial consonant mutations, which alters the initial consonant of a word in regular ways depending on grammatical context. So in Welsh, while ‘Wales’ is Cymru, ‘Welcome to Wales’ is Croeso i Gymru, ‘in Wales’ is yng Nghymru and ‘England and Wales’ is Lloegr a Chymru. This is interesting enough, but not the only way that the start of a word may be altered in languages. Indeed, we don’t even have to leave English to find examples of a different phenomenon that can take place in the history of an individual word.

Let us take a word like adder (the snake specifically, not someone that does addition!). We can look for cognates in closely-related languages, but we are immediately presented with a problem: German Natter, Frisian njirre and Icelandic naðra all seem like they should be related (all being words for ‘snake’), but what’s with this n- at the beginning of the word? Things only get more confusing when we notice words like Latin natrix ‘watersnake’, Welsh neidr or Scottish Gaelic nathair, all again showing an n-. Finally, when we look at Old English we find that the word there is næddre! What’s going on? We know that in general English n- doesn’t do anything particularly strange and it certainly doesn’t just disappear from the beginnings of words, as evidenced by numerous forms like name, night, nest, new, and nine which have had an n- since Proto-Indo-European!

The answer lies in a phenomenon that linguists call ‘rebracketing’. This is a fairly straightforward notion; linguists already make use of brackets to show the internal structure of phrases, thus any change in the structure of the phrase is notated by a change in the arrangement of the brackets. (It will be noted that some authors, including the Oxford English Dictionary, use the term metanalysis instead, but the meaning is the same.)

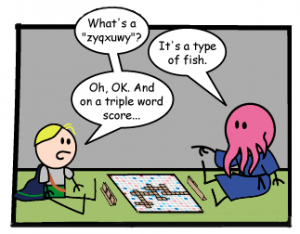

In the case of adder, the confusion comes from the indefinite article, which in English is a before words beginning with a consonant and an before words beginning with a vowel. Thus, if a word begins with an n-, this can find itself being rebracketed onto the indefinite article: thus [a [nadder]] becomes [a-n [adder]]. And this isn’t the only word where this has happened in English either: thus [a [napron]] (from French napperon) became [a-n [apron]]. On the flipside, the opposite is also found, where the -n from the indefinite article finds itself attached to the front of a word that originally began with a vowel, e.g. [an [ewt]] → [a [n-ewt]] or [an [ekename]] → [a [n-ickname]].

Some of these forms have since become the predominant forms of their respective words, but such is not always the case. For example, uncle derives from a French word oncle, ultimately from Latin avunculus. However, those who are familiar with their Shakespeare will remember the Fool in King Lear, who refers to the title character as ‘nuncle’. Here the reanalysis, rather than from the indefinite article, seems to have been on the basis of possessive pronouns mine and thine, which are particularly frequently used with kind terms: thus [mine [uncle]] becomes [my [nuncle]]. Yet, unlike with the other examples, this has not stuck around, perhaps because the other possessive pronouns (his, her, our, your, their) which would not have motivated this reanalysis; thus the original uncle stuck around and was able to reassert itself.

Nor is English alone in exhibiting these kinds of change. In the adder~nadder case, the same reanalysis has also taken place in Dutch and Low German, also spelt adder in both cases. Similarly, Arabic nāranj was borrowed into Spanish as Naranja, but this underwent rebracketing when it was borrowed into Italian as arancia, and it was from there that the word spread to the rest of Europe, including English orange.

French provides us with an especially interesting example of layered reanalyses in a single word. In Old French, unicorne was reanalysed as beginning with the indefinite article (which is in a sense not incorrect: the literal meaning of the word is ‘one-horn’ and ‘one’ is the source of the French indefinite article, as well as indefinite articles in general cross-linguistically). This left a form icorne, which would contract with the definite article, giving l’icorne ‘the unicorn’. However, at some point, this contracted form with the article came to be reanalysed as the base of the noun itself, with the result that licorne is now simply the French for ‘unicorn’, leading to constructions such as la licorne ‘the unicorn’ where a historical definite article appears ‘doubled up’!

Some of the most complex cases of rebracketing can be found in Scottish Gaelic. Here we have a number of potential sources of rebracketing, both because the definite article changes depending on the following noun and because of the interaction of the definite article and the mutation system.

Firstly, with vowel-initial masculine noun the definite article prefixes a t- e.g. eun ‘bird’ but an t-eun ‘the bird’. Unsurprisingly, based on the examples we have seen above, this prefixed t- has in many cases become attached to the noun. Interestingly this is particularly common in loanwords from Old Norse, such as talla ‘hall’ from hǫll, tòb ‘small bay’ from hóp (òb is also common) and tolm ‘small islet’ from holmr, as well as other loans such as taigeis ‘haggis’ and tobha ‘hoe’ from English.

In a similar vein, one of the components of consonant mutation is Scottish Gaelic is that an f sound disappears (though is still written as fh). As a result, a larger number of words that began with vowels in Old Irish have acquired an f- in Scottish Gaelic, e.g. áinne ‘ring’, uar ‘cold’ and íaru ‘squirrel’ have become fáinne, fuar and feòrag respectively, as if an áinne uar ‘the cold ring’ was really an fháinne fhuar. Many of the words have undergone the same kinds of changes in Irish and Manx, though not all languages agree on which (e.g. Irish also has fáinne and fuar but iora respectively).

And, as in English, words that begin with n- can find this consonant being rebracketed as part of the article an. However, once this n- has been rebracketed, this now vowel-initial word can undergo the same kinds of mutation-based reshaping as an originally vowel initial word. Perhaps the most extreme example of this is ‘nettle’, which was nenaid in Old Irish, but in Scottish Gaelic can be (depending on who you ask) any of neanntag, eanntag (with the n- rebracketed away), feanntag (with the f- appended by lenition reversal) and deanntag (where the d- is apparently a hypercorrective reversal of a process of nasalisation in the Northwestern dialects)!

So, when searching around for a word in a dictionary or an old text, be cautious; simply looking for the first consonant to give you a clue might be misleading when taken out of context. Furthermore, instances like these make clear that language is primarily a spoken phenomenon and the kinds of changes that we see reflect that: while in a written text the different between a newt and an ewt is obvious, in spoken language the question of where one word ends and the nexts begins is not so straightforward as a casual glance at a dictionary might suggest. Perhaps this should then make us ponder further how much written language is a direct reflection of spoken language versus being at least partially arbitrary choices made by the writers.