Drinkable houses, edible canoes and Trojan horses

Michael Lotito, a French entertainer known as Monsieur Mangetout, became famous for his penchant for devouring objects that most would consider inedible. From bicycles and televisions to the most bizarre of all, a Cessna 150 light aircraft.

Though Monsieur Mangetout hailed from France, one might have thought that he was from the archipelago of Vanuatu. This small island nation is not only famous for being the most linguistically dense country in the world – with over 130 languages for a population of just a quarter of a million – but is also renowned for its intriguing possessive classifiers, which turn up in sentences when you talk about the things that you own, much like the possessive pronouns in English – my, your, hers etc. But in the Oceanic languages of Vanuatu these classifiers also tell us about how you will use the item that you own.

The most common distinctions these classifiers make are between three types of possessions: ones that can be drunk, eaten and a residual classifier used when the more specific instances of eating and drinking aren’t needed. So, for example if you speak Paamese you can make a distinction between a coconut that you will drink, ani mak ‘my drinkable coconut’; one that you will eat the flesh of, ani ak ‘my edible coconut’; or one that you intend to sell, ani onak ‘my coconut for an unspecified use’.

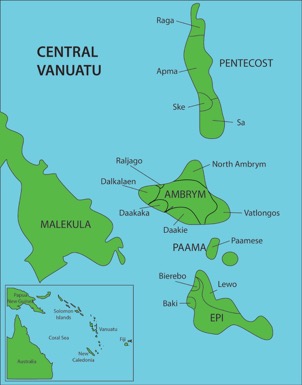

But, more intriguingly, several languages of Central Vanuatu, spoken on the islands of Pentecost, Ambrym, Paama and Epi, use the food and drink classifiers for some rather strange items that one might not consider to be edible or drinkable — though of course Michael Lotito might beg to differ. The drink classifier in the language of North Ambrym covers a rather broad range of entities, including the obvious drinks such as water, tea, coffee and juice:

(1) ma-n we / ti / jus DRINK.CLASSIFIER-his water tea juice ‘his water/tea/juice’

But the classifier is also used with items that can’t be drunk, like the words bwelaye ‘cup’ or bwela ōl ‘coconut shell (used as a cup)’, but also im ‘house’, hul ‘mat’ and bulubul ‘hole’. And in the Sa language spoken on Pentecost island, the food classifier can also be used with the word bulbul ‘canoe’!

How do you drink a house? How do you eat a canoe? While Michael Lotito might well be able to eat canoes and drink houses, the people who speak these languages certainly do not! So what explanation can be given as to why and how these non-drinkable and non-edible entities are included within the semantic domain of drinks and food?

The words meaning cups and containers of liquids are included with the drink classifiers in some of these languages due to a process of semantic extension. This is when the coverage of the semantics of a classifier are extended to include entities that are frequently associated with the core meaning of that classifier. This type of semantic extension is known as metonymy, where the word for a container can be used instead of the word for what it contains – e.g. in English we can use the word ‘dish’ to refer not only to a plate, but also to its contents. It is not such a large cognitive step to associate drinks with cups, and that is why containers of liquids are now included in the drink classifier’s semantic domain. However, it is quite a large cognitive leap to think that houses are associated with drinks and canoes with food.

To explain how houses are now classified along with drinks and canoes with food we have to look into the history of the languages and how these languages have changed through time. This is of course quite a difficult endeavour considering that these languages have no literary traditions and are only now just starting to be written down. We cannot consult old texts to see how the language used to be several hundred years ago as these don’t exist. Though limited records exist for a few languages going back to the mid 1800s, we mainly have to rely on comparing how related languages in the area differ and try to figure out how they got to be different.

Let’s start by looking at the language of Apma, spoken on Pentecost. The word for house, imwa, doesn’t occur with the drink classifier, but instead occurs in a different possessive construction where the owner is marked directly on the word for house, instead of on a classifier:

(2) imwa=n atsi house=his person ‘a person’s house’

This type of construction, called direct possession, normally occurs with possessions closely associated with the possessor, including body parts and kinship terms, but sometimes includes more intimate personal possessions as well. Now if we look at Apma’s neighbouring language, Ske, spoken to the south, the noun for house occurs with the drink classifier:

(3) im mwa=n azó house DRINK.CLASSIFIER=his person ‘a person’s house’

As you can see the word for house in Ske, which historically for the languages of Pentecost would have been imwa just like it is in Apma, has been split, where the first part im now means ‘house’, and speakers recognise the second part of imwa, namely mwa, as identical in form to the drink classifier. Speakers have now reanalysed the second part of the word for house as being the drink classifier, and now accept houses as being classified along with drinkable entities. A similar mechanism has occurred across several other languages of Central Vanuatu, and this is why houses are classified along with drinks.

In most languages of Vanuatu this change didn’t occur and houses are either directly possessed or occur with the residual general classifier. But in a few other languages, the word for house developed into a distinct classifier that is different from the drink classifier. In the languages of Southern Vanuatu the word for house iimwa has now turned into a classifier for locations and places, and is distinct from the classifier for drinks — nɨmwɨ.

Now what about the edible canoes that I mentioned earlier? This strange occurrence happens in the language of Sa, also spoken on Pentecost island:

(4a) a-k anian (b) a-k bulbul FOOD.CLASSIFIER-my food FOOD.CLASSIFIER-my canoe ‘my food’ ‘my canoe’

Historically, the word for canoe was waga in Proto Oceanic, and the word for bulbul was used for a specific type of canoe. Sometimes linguists get lucky and there can be historical documents that help show us the way. Miss Hardacre, a missionary living in northern Pentecost in the early part of the twentieth century, made a small dictionary of the Raga language. In this dictionary she recorded the generic-specific word pairing waga bulbul, ‘canoe type/raft’. Now in Sa, the original word for canoe, waga, underwent several sound changes until it ended up looking like the food classifier, where only the medial vowel /a/ was left! The new word for canoe was bulbul, whereas the old generic term, waga, merged into the food classifier. In other languages of the area, such as Raljago, spoken on Ambrym, a separate classifier for canoes and boats emerged, distinct from the food classifier. Thus, the food classifier is a, but the canoe classifier is ai.

Sometimes when a merger takes place, the noun that merges into a classifier acts as a Trojan horse. Looking back to the language of North Ambrym, where the drink classifier can occur with other nouns denoting houses, parts of houses, and mats. The word for house that originally merged into the drink classifier acts as a locus for semantic extension, opening a back door to other nouns that are semantically similar — those that are in the domain of houses — to enter into the drink classifier as well.

I think Michael Lotito would have felt at home speaking one of the Oceanic languages of Vanuatu. He might even have said of his Cessna 150ː

(5) a-k Cessna 150 FOOD.CLASSIFIER-my Cessna 150 ‘my edible Cessna 150’

Many thanks to Andrew Gray who runs the languages of Pentecost Island website and is my co-conspirator in turning this post into a journal article!