Who are the Germans?

You may be familiar with the fact that the Germans refer to themselves as Deutsch and their country as Deutschland, and we find this term also in most other Germanic languages, such as Dutch Duits or Swedish Tysk, as well as Italian Tedesco. However, there are many other names in other parts of Europe. The French and Spaniards call them Allemand/Alemán, as do the Welsh with Almaenaidd; the various Slavic languages share a different term again, seen in e.g. Polish Niemiec or Russian Nemets. In the Baltic the Lithuanians and Latvians have their own terms not seen anywhere else (Vokietis and Vācijis respectively), while in Finland and Estonia they call them Saksi. We could also add some assorted forms from smaller languages, such as Miksas from Old Prussian, an extinct sister language to Lithuanian and Latvian.

Now, it is not unusual for inhabitants of a country to refer to themselves and their country with a different form from that used by outsiders (when was the last time you called China Zhongguo or India Bharat?). What is particularly notable about the German case, however, is the diversity even among its immediate neighbours. Contrast e.g. France, where everyone uses some form of derivative of Latin Francia (after the Germanic tribe the Franks), though the Greeks still call it Gallia after the Roman province of Gaul. Similarly, most call Spain some form derived from Hispania and Italy one from Italia. So, this diversity in names for the Germans requires some explanation.

Whence this plethora of terms? A consideration of history leads us to our answer. Recall that the modern country of Germany is a relatively recent creation, only being officially united in the mid 19th century by Otto von Bismarck. While there was a political entity that occupied the area in the form of the Holy Roman Empire it was only a relatively loose collection of small states, and prior to that the area was inhabited by a number of distinct Germanic-speaking peoples.

As a result, some of these names derive from the individual groups or tribes which lived in part of the area: so in the Western Romance and Brittonic Celtic languages the name of the Alemanni tribe was applied to the Germans as a whole. The same process occurred in the northeast with the Baltic Finns and the Saxons: not only were the Saxons the nearest group, but also, due to a combination of the Hanseatic League controlling trade through the Baltic and the anti-pagan crusading of the Teutonic Knights (another Deutsch-relative, see below), many Saxons came to settle in the Eastern Baltic, with some of their descendants still living in Estonia and Latvia today. Some small varieties show different groups again: some of the smaller Germanic varieties use a form derived from Prussian, after the state which ended up uniting the German peoples.

English takes a slightly different approach, deriving the term Germans from the Latin name of the region; Germania. This term included two Roman provinces covering much of modern-day Belgium, Switzerland, parts of eastern France and the Rhineland in modern Germany, as well as applying to the larger swathe of barbarian territories further east. Interestingly, several languages use this term to refer to Germany the country despite using a different term to refer to the Germans: Italian and Russian are the most notable examples.

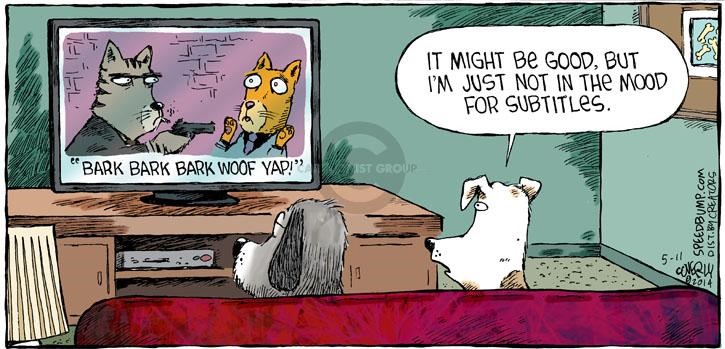

We find a different source again with the Slavic Nemets terms. There is again some dispute in origin, but the general consensus is that it derives from a Slavic root *němъ meaning ‘mute’, itself of contested origin. The meaning likely was not ‘mute’ necessarily, but rather simply denoted that these groups were not Slavic-speaking. This puts in a similar group to the word ‘barbarian’ in fact, which derives from a Greek word meaning ‘those who go bar-bar/talk incomprehensibly’. Similar origins to do with ‘talking’ are likely behind the Baltic Vok-/Vāc-/Miks- forms as well.

Finally, what of German ‘Deutsch’? Well, as is the case with many endonyms it is a relatively simple and self-referential etymology. It ultimately derives from an Indo-European root *tewteh2 meaning simply ‘people’, which shows up also in e.g. Irish túath with the same meaning. This form may also be the source of Romance forms such as Spanish todo or French tout meaning ‘everyone/everything’. This root even survives in Slavic, in Russian giving the form čužoj, meaning ‘foreign, alien’. This ended up as Germanic *þeudō, which through an adjective formation *þiudiskaz meaning something like ‘of the people’ ultimately leads to the modern German form. This form also gives Latin Teutones, a likely Celtic or Germanic tribe which lived in the North German region and was encountered by the Romans early in their expansion northwards.

So, as with many other terms, such as the aubergine words which have been discussed here before, the differences between languages are reflective of a complex history. In this case the wide array of disparate terms of different etymologies reflects the complex history of the entity involved, specifically the absence of a country that even called itself ‘Germany’ until the modern era, as well as the extent to which different groups of ethnic Germans have moved about in Europe.

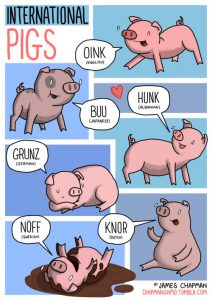

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by