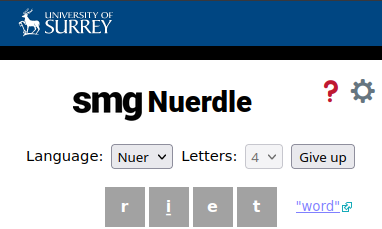

Linguistic fieldwork in the Russian Federation

Surrey Morphology Group, despite being a relatively small research group, nevertheless conducts linguistic fieldwork on all (inhabited) continents. Countries where members have worked over the years include Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Nepal, Nigeria, Russia, Serbia, and Vanuatu. Fieldwork in every region has its peculiarities, not necessarily connected to the linguistic properties of the language(s) studied, and it is the peculiarities of one such region which I would like to discuss today.

My personal fieldwork experience has involved several different regions of Russia, in the republics of Daghestan, Mari-El, Komi and Khakassia. Each of these regions has been fascinating in its own way, but Daghestan takes the lion’s share of the fieldwork I do. It is a mountainous region in the south of Russia stretching from the Caspian Sea to the Caucasus. It has borders with Azerbaijan and Georgia to the south, and within the Russian Federation it is next door to Chechnya. Medieval geographers described the Caucasus as “a mountain of tongues”, and with good reason. There are over forty languages spoken in this relatively small territory (just 50,300 sq km), and most of the linguistic diversity lies within an even smaller mountainous region in the south of Daghestan, involving languages of the indigenous Nakh-Daghestanian family.

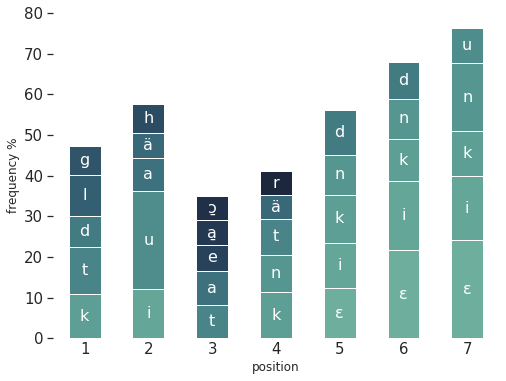

I wrote before about the linguistic interest of the language I have worked with the most, Archi (in many respects a typical representative of the family), but today I want to talk about social and cultural aspects of the work.

Culturally, Daghestan is a relatively homogeneous region; traditionally people lived in small villages, bred sheep and grew sturdy grains like rye and barley. Before the 20th century, many villages were organised as follows: there was one central village where people got together during summer months while the sheep were in the alpine pastures and did not need shelter during the night, and in winter months the people would go to smaller hamlets where the sheep (split into smaller groups) were kept in the houses or in underground sheepfolds made in the caves. The name for these winter sheepfolds is the same across several Daghestanian languages, so we can safely assume this was common practice for a long time.

After the Revolution of 1917 and the creation of the Soviet Union, many people got the opportunity to drive the sheep to regions with a milder climate near the Caspian Sea, and these shepherding practices ceased to exist. The smaller hamlets either disappeared or grew into proper villages, and in the latter case developed some dialectal differences. The people like to notice those differences but at the same time they still often perceive the conglomerate of the central village and the “hamlets” (which in some cases are even larger than the central village) as a single village.

Besides sheep breeding, Daghestanian people grew grain, and traditionally they would roast grains and make flour out of them. That flour can be mixed with water and then eaten directly, and in some villages they still make this “shepherd’s food” (they call it “old time instant noodles”). There were also many traditional crafts, among which are the silver products of Kubachi, wood inlaid with silver from Untsukul, Lezgian knitted slippers and earthenware from Balkhar.

From a sociolinguistic point of view, the Daghestanian languages were in a much better state during the 20C than many other smaller languages of Russia. Although only a handful of Daghestanian languages were recognised by the state and therefore taught at school, children in smaller language communities remained monolingual until well into their teens. Most Daghestanian people belonging to smaller language groups also speak the language of a larger Daghestanian neighbour (such as Avar, Dargwa or Lezgian) and one national language, whether Russian, Azeri or Georgian, although in the last 50 years Russian has been steadily coming to replace the others. The first thing that strikes a linguist who comes to Daghestan (especially if that linguist has experience of working with small languages in other parts of the Russian Federation) is how proud the people are of their languages, how ready they are to share them, how much delight they take in their complexity. Indeed, since they all speak at least one other language, they can well see that their languages are more complex, at least phonetically (for example, Archi has 70 consonants).

Some places in Daghestan have kept their traditional ways better than others: thus, in 2004, when I first came to Archi, I was really fascinated to see many women wearing traditional clothes and jewellery not only on special occasions but every day.

Living in people’s houses, I could see that they used traditional cots for babies and had retained most of the old practices connected with childbirth. For example, right before having her first baby, the woman goes to her mother’s house and stays there for the first 40 days of the baby’s life, being completely looked after (very often she just stays in bed). After 40 days, she moves back to her and her husband’s house in a very colourful procession: the whole thing is called “moving of the cot”.

But maybe the most important cultural characteristic of Daghestan is the living cultural practice of protecting one’s guests. Stemming from old times when travelling in the Caucasus mountains was not always safe, if one happens to come to a Daghestanian village one will be invited into a house, given food and shelter and will become kunaks with the master of the house. Kunak is not easy to translate. It means ‘guest’, but also ‘friend’. So I can say “I have a kunak in that village” meaning there is a person there who once was my guest (or vice versa) and now we are friends, so I can always count on having food and shelter in his house as much as he can in mine. In former times it was a duty for the master of the house to protect his kunak such that if anything were to happen to him, the perpetrator of the bad deed would answer to the house where the guest was staying. This system is still very much alive in Daghestan, and once I had eaten or slept in somebody’s house, I knew that I would be safe in that village and probably the neighbouring ones too.