The stretchiness of Oceanic possessive classifiers

In many of the Oceanic languages, if you want to talk about someone’s tomatoes you have to use a special word that tells you how the owner of the tomatoes intends to use them. These special words – possessive classifiers – centre around culturally important interactions. You can’t simply say ‘his tomatoes’ but have to say something like ‘his tomato [which he will eat]’ or ‘his tomato [which is on his land]’.

Here’s a couple examples from Vatlongos, spoken in Vanuatu:

Tomato an ‘his tomato [to eat]’

Tomato san ‘his tomato [growing on his land]’

Tomato nan ‘his tomato [for other purposes]’

What’s really interesting is that as there are so many languages within Oceania– around 500 – there is lots of variation in how speakers use the classifiers with various possessions. Some languages are really stretchy, in that a possession can occur with many different classifiers as long as the speaker can think of a plausible situation or context – just like in Vatlongos above. Other languages are less stretchy and somewhat sticky, in that a possession can only ever occur with one classifier. So, in North Ambrym (Vanuatu), as we will see more of below, the word for tomato would only ever be edible regardless of differing contexts.

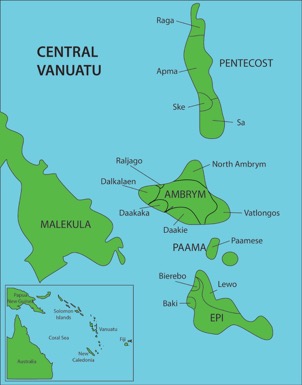

As part of our project on Optimal Categorisation we tested speakers from six different Oceanic languages on how sticky and stretchy their possessive classifiers are. We looked at Merei, Lewo, Vatlongos, North Ambrym (Vanuatu), Nêlêmwa and Iaai (New Caledonia). Each of these languages has a different possessive classifier inventory, from 2 (Merei) to 23 (Iaai). In order to test their stretchiness, we created video clips of people interacting with different objects and asked the speaker to describe what was happening with reference to the person’s possessions.

Some of the contexts we wanted to test were a bit strange as we wanted to see if speakers would use the classifiers in the same manner for both typical interactions (like the videos of drinking and washing with water above) and atypical interactions (like eating coffee or drinking raw eggs!). This way speakers would be confronted with strange situations that wouldn’t normally occur in their culture (or anyone’s culture for that matter – seriously who drinks raw eggs anyway?).

A well-behaved possessive classifier system should allow the same word used for a possession to occur with a different classifier depending on the various contexts.

For brevity’s sake let’s just look at two languages from our sample – Lewo and North Ambrym – spoken on the neighbouring islands of Epi and Ambrym in Vanuatu. With very typical interactions like drinking water and washing with water the speakers of Lewo changed the classifier to match the interactional context. For drinking water, all 20 speakers tested used the drinkable classifier along with the word for water. Similarly, for washing with the water, the vast majority of speakers, 16 out of 20, used the general classifier along with the word for water. This is pretty much what we expect from a well-behaved classifier system where a drinking context evokes the drinkable classifier, and a more general context evokes a general classifier.

What about more atypical interactions? – let’s compare the videos of someone eating eggs (typical) and the video of the man drinking eggs (very atypical!). For the speakers of Lewo all 20 used the edible classifier when talking about someone eating eggs. For the drinking eggs context only 9 speakers used the drinkable classifier, with the rest either using an edible classifier or the general classifier.

The classifier system of Lewo works well for typical interactions (stretchy!), but not so well for atypical interaction (a little bit stretchy and a little bit sticky!).

Now let’s compare Vatlongos to North Ambrym. For both the typical interactions of drinking and washing with water our 23 North Ambrym speakers gave the drinkable classifier. What? This is not what we expected! We expected that there would be a shift to the general classifier for the video of the man washing with water. North Ambrym is not behaving like an exemplary classifier system – it is much stickier than Lewo’s system.

What about atypical interactions? For the video of the person eating eggs, all speakers used the edible classifier, as expected. For the atypical drinking of eggs, 21 out of 23 speakers gave the edible classifier too! So a very sticky result with speakers using the same classifier regardless of the contextual interaction.

So what do our results show? That the classifier system in Lewo functions more like a well-behaved classifier system than North Ambrym’s does. Lewo’s classifier system behaves well in typical everyday situations, but not so well in atypical situations where speakers must make judgements on the fly. North Ambrym however, doesn’t look at all like a well-behaved classifier system. On the stretchiness-stickiness scale, North Ambrym is much more on the sticky side than Lewo is.