Is twote the past of tweet?

Have you ever encountered the form twote as a past tense of the verb to tweet? It is something of a meme on Twitter, and a live example of analogy (and its mysteries). However surprising the form may sound if you have never encountered it, it has been the prescribed one for a long time:

https://twitter.com/Twitter/status/47851852070522880?s=20

Ten years later, the question popped up among a linguisty Twitter crowd, where a poll again elected twote as the correct form:

Past tense of “I tweet”?

— Emmett! (@WannabeLinguist) July 27, 2021

It is clear that this unusual form replacing tweeted is some sort of form, but why specifically twote? I saw here and there a reference to the verb to yeet, a slang verb very popular on the internet and meaning more or less “to throw”. Rather than a regular form yeeted, the past for to yeet is often taken to be yote. The choice of an irregular form is probably meant to produce a comedic effect.

Yeet -> yote

Tweet -> twote— D2 Postin' ⬛️⬜️🟪 (@destiny_thememe) July 11, 2021

This, precisely, is analogical production: creating a new form (twote) by extending a contrast seen in other words (yeet/yote). Analogy is a central topic in my research. I have been trying to answer questions such as: How do we decide what form to use ? How difficult is it to guess? How does this contribute to language change?

But first, have you answered the poll?

Here at the SMG we need to know:

What do you think the past tense of 'I tweet' is?— Surrey Morphology (@SurreySMG) September 7, 2022

What is the past tense of “to tweet”?

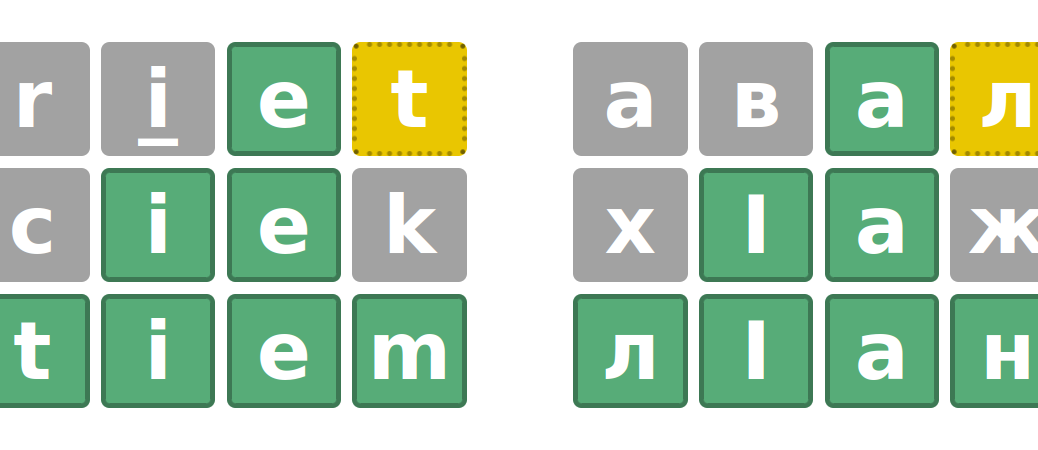

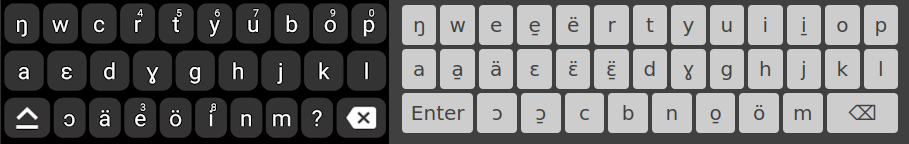

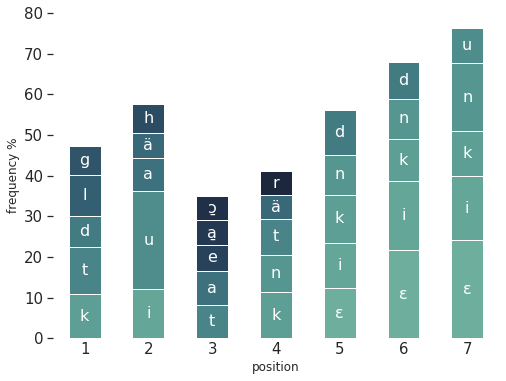

To investigate further why we would say twote rather than tweeted, I took out my PhD software (Qumin). Based on 6064 examples of English verbs1, I asked Qumin to produce and rank possible past forms of tweet2. To do so, it read through examples to construct analogical rules (I call them patterns), then evaluated the probability of each rule among the words which sound like tweet.

https://twitter.com/cavaticat/status/1212056421082251265

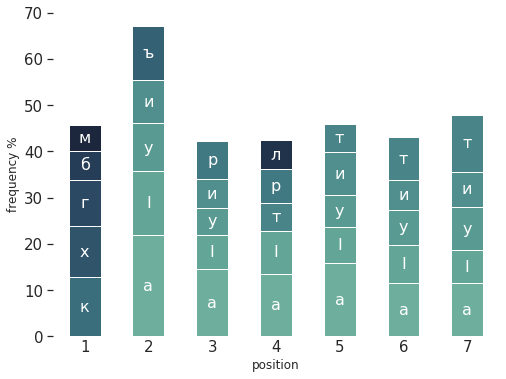

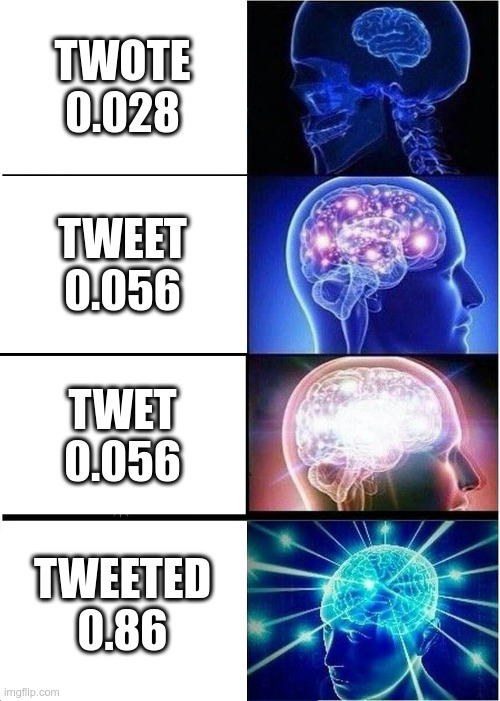

Qumin found four options3: tweeted (/twiːtɪd/), by analogy with 32 similar words, such as greet/greeted; twet (/twɛt/), by analogy with words like meet/met; tweet (/twiːt/) by analogy with words like beat/beat, finally twote (/twəˑʊt/), by analogy with yeet. Figure 1 provides their ranking (in ascending order) according to Qumin, with the associated probabilities.

As we can see, Qumin finds twote to be the least likely solution. This is a reasonable position overall (indeed, tweeted is the regular form), so why would both the official Twitter account and many Twitter users (including several linguists) prefer twote to tweeted?

speak / spoke

write / wrote

tweet / twote??

:/

:///— rax king (@RaxKingIsDead) August 31, 2018

But Qumin has no idea what is cool, a factor which makes yeet/yote (already a slang word, used on the internet) a particularly appealing choice. Moreover, Qumin has no access to semantic similarity, which could also play a role. Verbs that have similar meanings can be preferred as support for the analogy. In the current case, both speak/spoke and write/wrote have similar pasts to twote, which might help make it sound acceptable. Some speakers seem to be aware of these factors, as seen in the tweet above.

Is it twankt or twunkt? I'm thinking about the past-tense of tweet.

— Duncan Post (@BigDunkCan) September 1, 2022

What about usage?

Are most speakers aware of the variant twote and using it? Before concluding that the model is mistaken, we need to observe what speakers actually use. Indeed, only usage truly determines “what is the past of tweet”. For this, I turn to (automatically) sifting through Twitter data.

A few problems: first, the form “tweet” is also a noun, and identical to the present tense of the verb. Second, “twet” is attested (sometimes as “twett”), but mostly as a synonym for the noun “tweet” (often in a playful “lolcat” style), or as a present verbal form, with a few exceptions, usually of a meta nature (see tweets below). I couldn’t find a way to automatically distinguish these from past forms while also managing within the Twitter API limits. Thus, I left out both from the search entirely. This leaves only our two main contestants.

If it's not already been formally done, I should now like to declare the past tense of "tweet" to be "twet"

Today I "tweet", yesterday I "twet".

Hello? Webster? Funk and Wagnall?

Anybody there?— Bob Valvano (@espnVshow) May 24, 2019

Today I tweet, yesterday I ‘twet’ 😂😂😂😂😂😂. https://t.co/JHJleKDicg

— COCONUT 🥥🎶 -APRIL 5‼️ (@lijitimate) July 13, 2021

it is better to tweet and delete than to have never have twet at all

— Sylvie Borschel (@hellosylv) July 3, 2021

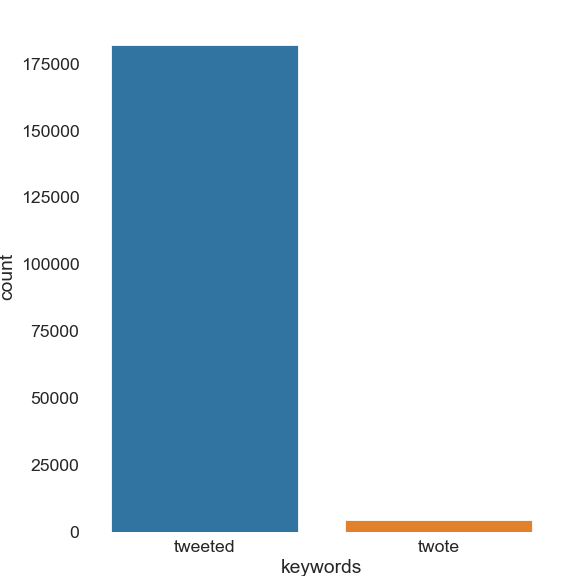

I extracted as many recent tweets containing tweeted or twote as Twitter would let me — around 300 000 tweets twotten between the 26th of August and the 3rd of September. 186777 tweets remained after refining the search4. Of these, less than 5000 contain twote:

As you can see, the tweeted bar completely dwarfs the other one. However amusing and fitting twote may be, and despite @Twitter’s prescription (but conforming with Qumin’s prediction), the regular past form is by far the most used, even on the platform itself, which lends itself to playful and impactful statements. This easily closes this particular English Past Tense Debate. If only it were always this simple!

- The English verb data I used includes only the present and past tenses, and is derived from the CELEX 2 dataset, as used in my PhD dissertation and manually supplemented by the forms for “yeet”. The CELEX2 dataset is commercial, and I can not distribute it. [↩]

- The code I used for this blog post is available here, but not the dataset itself. Note that for scientific reasons I won’t discuss here, this software works on sounds, not orthography. [↩]

- One last possibility has been ignored by this polite software, a form which follows the pattern of sit/sat. I see it used from time to time for its comic effect, but it does not seem at all frequent enough to be a real contestant (and I do not recommend searching this keyword on Twitter). [↩]

- Since there has been a lot of discussion on the correct form, I exclude all clear cases of mentions. I count as mentions any occurrences wrapped in quotations, co-occurring with alternate forms, mentioning past tense, or with a hashtag. Moreover, with the forms in –ed, it is likely that the past participle would be identical, but for twote, the past participle could well be twotten. To reduce the bias due to the presence of more past participles in the usage of tweeted, I also exclude all contexts where the word is preceded by the auxiliary forms has, have, had, is, are, was, were, possibly separated by an adverb. [↩]