Royal Rules on Rich Rectors

Last month, the Guildford Shakespeare Company put on a production of Richard II, a fascinating tale of political strife and the perils of having a leader lacking in competence when the country is in crisis. Sound familiar? In any case, this got me thinking about the name Richard and its many etymological links.

First with the name Richard. It’s borrowed from French, but it didn’t start there. In fact it is one of a number of French words that was borrowed from Germanic, deriving from Frankish *Rīkahard, meaning ‘hard/brave king’. This also gives modern German Richard and through the travels of the Goths and Vandals also made its way into Spanish as Ricardo and Italian as Riccardo. The first part of this name, the *rīk- ‘ruler’ part, in other derivations also gives words like German Reich and Dutch rijk, both meaning ‘empire’ or ‘kingdom’, which in English is also found as the ‘domain, kingdom’ suffix -ry, as in Jewry ‘the Kingdom of the Jews’. As different derivation again gives us English rich, something you’d rather expect a king to be. As a component of names it is ubiquitous in Germanic, such as in Old English Godric ‘God(ly) king’, Wulfric ‘Wolf-king’ and Theodric ‘King of the people’. This last one turns up in German as Dietrich and, again courtesy of the Franks, through French Thierry comes into English as Terry (see also my previous post on the Germans for more on this Theod-).

But it is not only Germanic languages that have this root. Indeed, some form of it crops up across the Indo-European language family, usually meaning something like ‘king’ or ‘ruler’. In Celtic (from which Germanic likely borrowed the rīk- words) we find e.g. rí in Irish and rhi in Welsh, both meaning king. In Gaulish, rulers such as Vercingetorix and Ambiorix had an earlier form –rix it as part of their name, and in a reduced form we find the same in the Welsh surname Tudor, originally meaning ‘ruler of the people’ and thus cognate with Theodric/Dietrich/Terry.

In Latin too we find rēx, again meaning ‘king’ or ‘ruler’. This form survives as such in many modern Romance languages, for example Spanish rey and French roi. We also get two separate adjectives in English: regal from Latin and royal from French. Further afield, we find this word cropping up as far away as India, in the form of Sanskrit rāja, once again a ‘king’ word, as well as rāṣṭrá, a ‘kingdom’.

All of these forms can be traced back to a form in Proto-Indo-European (the reconstructed ancestor of all of these languages), which we represent as *h3rḗǵs. In the terminology of Indo-European studies this is an ‘athematic root noun’, meaning a short root without additional derivational suffixes onto which inflectional endings such as the nominative singular *-s are suffixed directly, rather than having an additional ‘theme vowel’ *-o inbetween. As with many such forms in Proto-Indo-European, when we isolate the root itself, *h3reg-, which probably meant something like ‘stretch out the arm, direct’, we can find even more related derivations.

Adding a thematic vowel *-e/o- we get a verb which shows up in Latin as regō ‘rule, govern, direct’, along with an array of derived nouns which we have inn English. We have the agent noun rector, the instrument noun rule (from a French reflex of Latin rēgula) and the abstract noun regimen. Additionally, we have prefixed verbs such as dīrigō, ērigō and corrigō, which through their respective supine forms dīrēctum, ērēctum and corrēctum give us English ‘direct’, ‘erect’ and ‘correct’ respectively.

Germanic, meanwhile, provides us with a different set of reflexes of this verb. While we have already seen the rich set relating to wealth and kingship, the ‘straighten’ meaning of *h3reg- results in other interesting links. We have the (originally separate) verb and noun rake, a device for making straight lines, and the former participle right, originally meaning ‘straightened, directed’. Then we have reckon, perhaps a natural extension of the metaphor of lining things up in order to count them. Finally, from a causative ‘make straighten up’ we have reach (as if ‘straightening out one’s arm’).

This here is the greatest joy of etymology for me; by untangling these webs of relationships, we can show how so much of our vocabulary results from variations upon a common root. It reminds us of the continual creativity involved in using language and, by extension, the creativity of language users, i.e., humans.

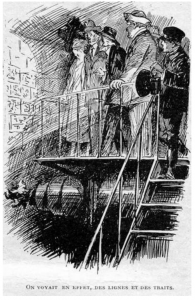

Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well.

Leon Groc’s Le deux mille ans sous la mer (‘2000 years under the sea’), from 1924, starts out with our heroes supervising the construction of a tunnel under the English Channel. They discover a mysterious inscription on a rock face. Fortunately, one of the party is a philologist, and identifies it as Chaldean (i.e. a form of Aramaic)! And a particularly archaic variety at that. This impresses the rest of the party, at least as much as the content of the inscription itself: Impious invaders, you shall not go any further. However, a subsequent mining accident forces them to break through the rock, where they discover a cavern inhabited by race of pale blind people, descendants of Chaldeans (or to be more precise, speakers of Chaldean) who had sought refuge in that cavern from some long-forgotten disaster, only to discover they couldn’t find a way out. The learned philologist applies his practical knowledge of Chaldean in communicating them. I won’t spoil the fun for those of you planning to read it; but it does not go well. James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew:

James De Mille’s A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder from 1888 features members of a British expedition surveying the South Pacific becoming stranded in an unknown country with – once again – some cave dwellers, who call themselves Kosekin and speak a Semitic language. In the usual fashion of such stories in this period, there is a narrative within a narrative, in this case the manuscript directly relating the adventure, and the commentary of the members of the yacht party who discovered it. While the core narrator (named More) merely recognizes some affinity to Arabic, one of the members of the yacht party just so happens – once again – to have a philological background, which, after a lengthy digression on the comparative method and Grimm’s law, leads him to conclude that the underground race speaks a language descended from Hebrew: Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions:

Further proof of the power of historical linguistics in a tight situation comes from E. Charles Vivian’s City of Wonder (1923). Again in the South Pacific, a group of adventurers is attacked by a strange woman (speaking, of course, a strange language) in charge of a monkey army. Taking stock after having slaughtered the attackers, the narrator asks one of his companions: Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where

Back underground, Howard De Vere’s A Trip to the Center of the Earth, first published in New York Boys’ Weekly in 1878, is a story I haven’t been able to track it down yet, but from the description in E.F. Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years, it promises to be one of the high points in early dime novel treatments of historical linguistics. A pair of boys exploring Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave come across an underground world where Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)

Alongside lost race fantasies, futuristic science fiction is another obvious vehicle for literary forays into historical linguistics. Régis Messac’s Quinzinzinzili from 1935 is a particularly interesting variant, being – as far as I know – the only serious fictional treatment of contact linguistics. (Admittedly I haven’t looked elsewhere.) Set in the period after a fictional World War II which everybody in this interwar period seemed to be expecting anyway), its narrator is trapped in a post-apocalyptic world alone with a particularly annoying handful of pre-teens. (And thus probably the most gruesome post-apocalyptic story ever written.) They are largely French speakers, but there are Portuguese speakers and English speakers among them as well. They develop a sort of pidginized French, colored by a spontaneous sound changes such as the nasalization of all vowels, along with curious semantic shifts. The title Quinzinzinzili reflects this all, being their rendition of the second clause in the Lord’s Prayer in Latin (qui es in cœlis ‘who art in Heaven’), used as a name for their inchoate deity. I won’t say any more because I think everybody should read it. Way better than Lord of the Flies, which it preceded and superficially resembles. (And which has no noteworthy linguistic content.)