Words apart: when one word becomes two

As any person working with language knows, the list of words from which we build our sentences is not a fixed one but rather is in a state of constant flux. Words (or lexemes in linguists’ terminology) are constantly being borrowed (such as ‘sauté’ from French), coined (such as ‘brexit’ from a blend of ‘Britain’ and ‘exit’) or lost (such as ‘asunder’, a synonym for ‘apart’). These happen all the time. However, two more logical processes exist that can alter the total number of entries in the dictionary of our language. Occasionally, lexemes may also merge, if two or more become one; or split, if one becomes two. These more exotic cases constitute a window into the fascinating workings of the grammar. In this blog I will present the story of one of these splitting events. It involves the Spanish verb saber, from Latin sapiō.

The verb’s original meaning must have been ‘taste’ in the sense of ‘having a certain flavour’, as in the sentence “Marmite tastes awful”. At some point it also began to be used figuratively to mean ‘come to know something’, not only by means of the sense of taste but also for knowledge arrived at by means of other senses. It is interesting that in the Germanic languages it seems that it was sight rather that taste that was traditionally used in the same way. Consider, for instance, the common use, in English, of the verb ‘see’ in contexts like “I see what you mean”, where it is interchangeable with ‘know’. Whether the source verb can be explained by the differences between traditional Mediterranean and Anglo-Saxon cuisines I’d rather not suggest for fear of deportation.

In any case, what must have been once a figurative use of the verb ‘taste’ became at some point the default way of expressing ‘know’. These are the two main senses of saber in contemporary Spanish and of its equivalents in most other Romance languages. The question I ask here is: do speakers of Spanish today categorize this as one word with two meanings? Or do they feel they are two different words that just happen to sound the same? There may be a way to tell.

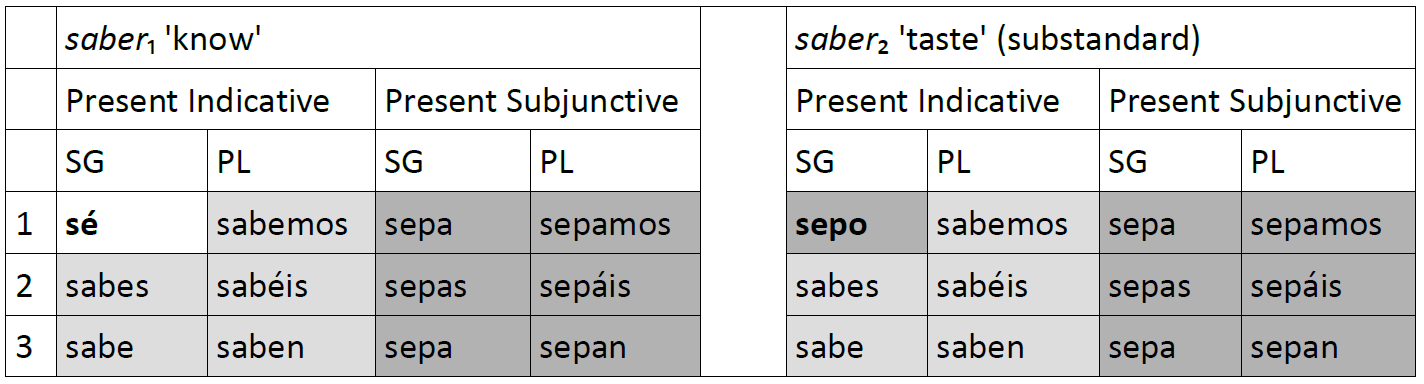

In Spanish, unlike in English, a verb can take dozens of different forms. The shape of a verb changes depending on who is doing the action of the verb, whether the action is a fact or a wish etc. Thus, for example, speakers of Spanish say yo sé ‘I know’ but tú sabes ‘you know’. They also use one form (so-called ‘indicative’) in sentences like yo veo que tú sabes inglés ‘I see that you know English’ but a different form (so-called ‘subjunctive’) in yo espero que tú sepas inglés ‘I hope that you know English’. The Real Academia Española, the prescriptive authority in the Spanish language, has ruled that, because saber is a single verb, it should have the same forms (sé, sabes etc.) regardless of its particular sense. Speakers, however, have trouble to abide by this rule, which is probably the reason why the need for a rule was felt in the first place. My native speaker intuition, and that of other speakers of Spanish, is that the verb may have a different form depending on its sense:

Forms of Spanish saber (forms starting with sab– in light gray, forms starting with sep– in dark gray)

Forms of Spanish saber (forms starting with sab– in light gray, forms starting with sep– in dark gray)

The most obvious explanation for why this change could happen is that, when the two main senses of saber drifted sufficiently away from each other, speakers ceased to make the generalization that they were part of the same lexeme. When this happened, the necessity to have the same forms for the two meanings of saber dissappeared. But, why sepo?

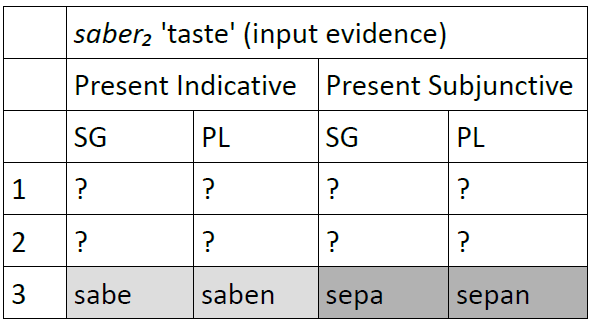

Because cannibalism is on the wane (also in Spain) we hardly ever speak about how people taste. As a result, the first and second person forms of saber (e.g. irregular sé) are only ever encountered by speakers under their meaning ‘know’. Because of this, they do not count as evidence for language users’ deduction of the full array of forms of saber₂. This meant that the first and second person forms of saber₂ ‘taste’, when needed (imagine someone saying sepo salado ‘I taste salty’ after coming out of the sea), had to be formed on the fly on evidence exclusive to its sense ‘taste’ (i.e. third persons and impersonal forms):

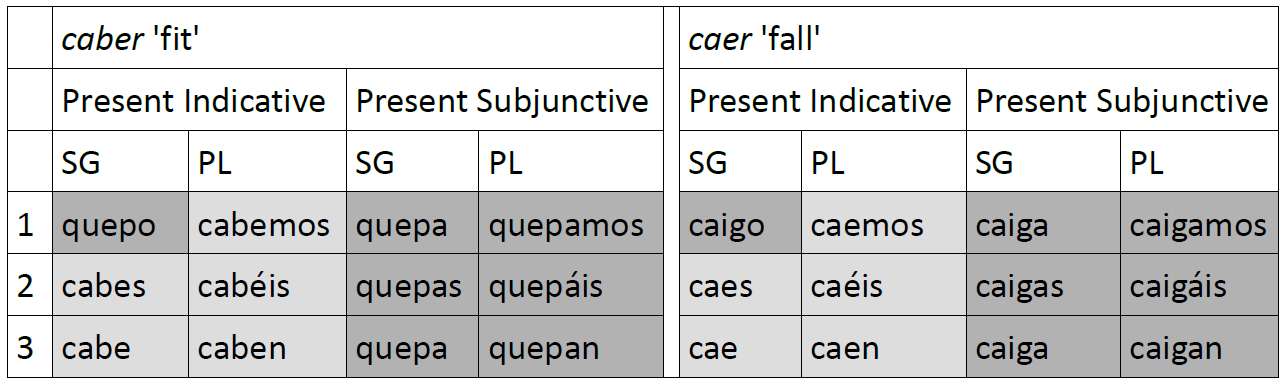

Because of the evidence available to speakers, at first sight it might seem strange that this ‘fill-in-the-gaps’ exercise did not result in the apparently more regular 1SG indicative form sabo. This would have resulted in a straightforward indicative vs subjunctive distinction in the stem. The chosen form, however, makes more sense when one observes the patterns of alternation present in other Spanish verbs:

Verbs that have a difference in the stem in the third person forms between indicative and subjunctive (cab- vs quep- or ca- vs caig-) overwhelmingly use the form of the subjunctive also in the formation of the first person singular indicative. This is a quirk of many Spanish verbs. It appears that, by sheer force of numbers, the pattern is spotted by native speakers and occasionally extended to other verbs which, like saber₂ look like could well belong in this class.

In this way, the tiny change from sé to sepo allows us linguists to see that patterns like those of caber and caer are part of the grammatical knowledge of speakers and are not simply learnt by heart for each verb. In addition, it gives us crucial evidence to conclude that, today, there are in Spanish not one but two different verbs whose infinitive form is saber. Much like the T-Rex in Jurassic Park, we linguists can sometimes only see some things when they ‘move’.