What slips of the tongue can tell us about language

“The grouchy knight cuddled the rowdy seer’s adorable puppy while devouring lasagne”

This is probably a sentence you’ve never heard – or produced – before. Yet this experience is not novel – everyday, you make utterances you’ve never heard, and understand new ones.

Producing such utterances is not a trivial matter. To do this we have to generate them – that is, decide on the concept to be expressed, encode that into words and structures, then into the sounds that make up our words before sending instructions to our articulatory apparatus to produce the utterance. All within fractions of a second.

Yet, sometimes we make mistakes, and produce things we didn’t intend to do:

| Error (The Mistake we Make) | Target (What we had intended to say) |

| heft lemisphere | left hemisphere |

| squoor | squeaky floor |

| a leading list | a reading list |

| gave the goy | gave the boy |

| stough competition | stiff/tough competition |

| she sliced the knife with a salami | she sliced the salami with a knife |

| a hole full of floors | a floor full of holes |

We usually notice these errors when we make them and correct ourselves. But rather than being merely slips of tongue, they are a goldmine of information as they demonstrate breakdowns at various parts in the speech production process.

Some of these errors are lexical selection errors – we select the wrong lexical concept or lemma for the message we’re trying to say. That is, we select the wrong word stored in our brains, we pick the wrong word from our mental dictionary. This can be simply the wrong concept, as in: ‘he’s carrying a bag of cherries’ instead of ‘grapes’. Sometimes, we can combine words together in blends: ‘the competition is getting a little stough’ instead of stiff or tough. Other times, we can exchange words within a sentence, as in ‘she sliced the knife with a salami’, rather than ‘she sliced the salami with a knife’.

We can also make phonological errors, that is, errors in the sound structure of our words:

| Exchanges | |

| heft lemisphere | left hemisphere |

| fleaky squoor | squeaky floor |

| cheek and ch[ɔː]se | Chalk and cheese |

| Additions | |

| enjoyding it | enjoying it |

| Deletions | |

| cumsily | Clumsily |

| Anticipations | |

| leading list | reading list |

| Perseverations | |

| gave the goy | gave the boy |

We can look at large data sets, or corpora, to see what kinds of errors are commonly made. We find that these errors are still well-formed in terms of their sound structure, or phonology. 60-90% of errors (depending on the corpus you look at) involve errors with a single sound or segment, and these errors are sensitive to syllable structure. That is, we might swap segments from the same part of the syllable as in exchanges:

face spood < space food

Or we might combine the beginning of one syllable and the end of another:

grool < great + cool

We also like to swap sounds that are similar to each other, so

paid mossible < made possible

is more likely than

two sen pet < two pen set

There are exceptions to these generalisations of course – but they are rare.

Speech errors give us an insight into normal speech production processes. The fact that sound errors occur at all tells us that speech production is a generative process – it is not that we just reproduce fully formed stored sentences, but rather we create each utterance afresh each time. In order to mix or swap two elements, both must be activated at the same point of the production process.

Furthermore, the range of speech across which errors can occur implies that the span of processing is greater than a single word. You might be familiar with spoonerisms, popularised by Dr William Archibald Spooner:

We must plan more than a word ahead for errors like these to happen.

There is a much wider array of questions we can ask about speech production than can be answered by speech errors, but certainly they are an entertaining place to start.

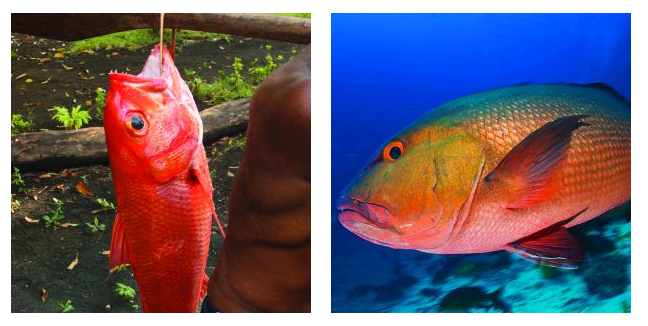

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?