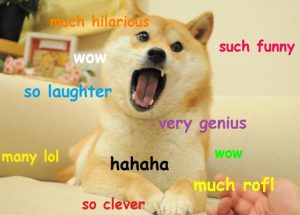

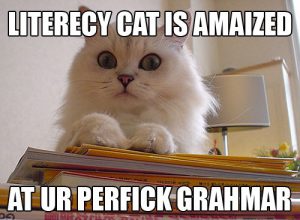

As is well known, animals on the internet can have very impressive language skills: cats and dogs in particular are famous for their near-complete online mastery of English, and only highly trained professional linguists (including some of us here at SMG) are able to spot the subtle grammatical and orthographic clues that indicate non-human authorship behind some of the world’s favourite motivational statements.

Recent reports suggest that some of our fellow primates have also learnt to engage in complex discourse: again, the internet offers compelling evidence for this.

But sadly, out in the real world, animals capable of orating on philosophy are hard to come by (as far as we can tell). Instead, from a human point of view, cats, dogs, gorillas etc. just make various kinds of animal noises.

Why write about animals and their noises on a linguistics blog? Well, one good answer would be: the exact relationship between the vocalisations made by animals, on one hand, and the phenomenon of human spoken language, on the other, is a fascinating question, of interest within linguistics but far beyond it as well. So a different blog post could have turned now to discuss the semiotic notion of communication in the abstract; or perhaps the biological evolution of language in our species, complete with details about the FOXP2 gene and the descent of the larynx…

But in fact I am going to talk about something a lot less technical-sounding. This post is about what could be called the human versions of animal noises: that is, the noises that English and other languages use in order to talk about them, like meow and woof, baa and moo.

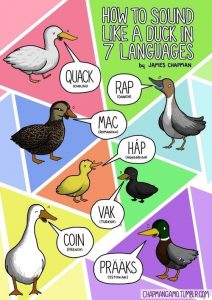

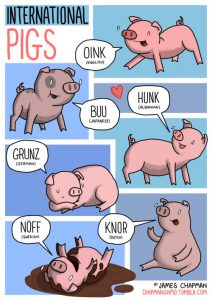

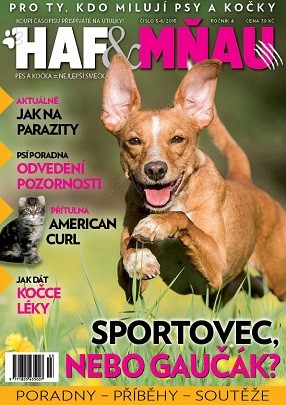

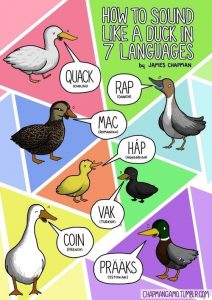

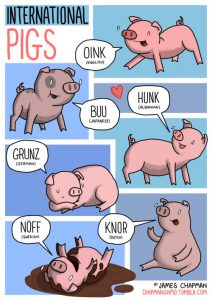

At this point you may be wondering whether there is much to be gained by sitting around and pondering words like moo. But what I have in mind here is this kind of thing:

These are good fun, but they also raise a question. If pigs and ducks are wandering around all over the world making pig and duck noises respectively, then how come we humans appear to have such different ideas about what they sound like? Oink cannot really be mistaken for nöff or knor, let alone buu. And the problem is bigger than that: even within a single language, English, frogs can go both croak and ribbit; dogs don’t just go woof, but they also yap and bark. These sound nothing like each other. What is going on? Are we trying to do impressions of animals, only to discover that we are not very good at it?

Before going any further I should deal with a couple of red herrings (to stick with the zoological theme). For one thing, languages may appear to disagree more than they really do, just because their speakers have settled on different spelling conventions: a French coin doesn’t really sound all that different from an English quack. And sometimes we may not all be talking about the same sound in the first place. Ribbit is a good depiction of the noise a frog makes if it happens to belong to a particular species found in Southern California – but thanks to the cultural influence of Hollywood, ribbit is familiar to English speakers worldwide, even though their own local frogs may sound a lot more croaky. Meanwhile, it is easy to picture the difference between the kind of dog that goes woof and the kind that goes yap.

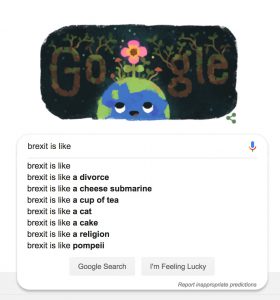

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by Saussure, is that most words are arbitrary: they have nothing inherently in common with the things they refer to. For example, there is nothing actually green about the sound of the word green – English has just assigned that particular sound sequence to that meaning, and it’s no surprise to find that other languages haven’t chosen the same sounds to do the same job. But right now we are in the broad realm of onomatopoeia, where you might not expect to find arbitrariness like this. After all, unlike the concept of ‘green’, the concept of ‘quack’ is linked to a real noise that can be heard out there in the world: why would languages bother to disagree about it?

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by Saussure, is that most words are arbitrary: they have nothing inherently in common with the things they refer to. For example, there is nothing actually green about the sound of the word green – English has just assigned that particular sound sequence to that meaning, and it’s no surprise to find that other languages haven’t chosen the same sounds to do the same job. But right now we are in the broad realm of onomatopoeia, where you might not expect to find arbitrariness like this. After all, unlike the concept of ‘green’, the concept of ‘quack’ is linked to a real noise that can be heard out there in the world: why would languages bother to disagree about it?

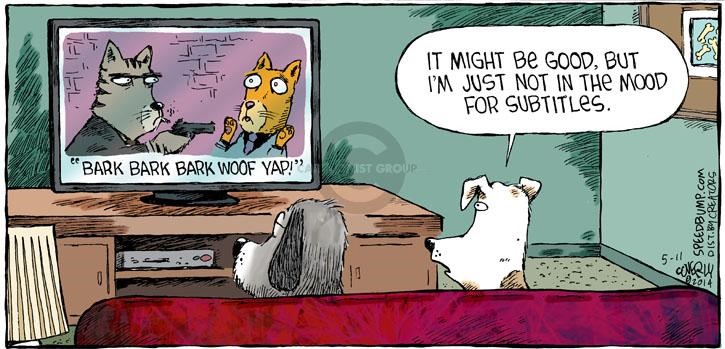

First off, it is worth noticing that not all words relating to animal noises work in the same way. Think of cock-a-doodle-doo and crow. Both of these are used in English of the distinctive sound made by a cockerel, and there is something imitative about them both. But there is a difference between them: the first is used to represent the sound itself, whereas the second is the word that English uses to talk about producing it. That is, as English sees it, the way a cock crows is by ‘saying’ cock-a-doodle-doo, and never vice versa. Similarly, the way that a dog barks is by ‘saying’ woof. The representations of the sounds, cock-a-doodle-doo and woof, are practically in quotation marks, as if capturing the animals’ direct speech.

This gives us something to run with. After all, think about the work that words like crow and bark have to do. As they are verbs, you need to be able to change them according to person (they bark but it barks), tense, and so on. So regardless of their special function of talking about noises, they still have to operate like any other verb, obeying the normal grammar rules of English. Since every language comes with its own grammatical requirements and preferences about how words can be structured and manipulated (that is, its own morphology), this can explain some kinds of disparity across languages. For example, what we onomatopoeically call a cuckoo is a kukushka in Russian, featuring a noun-forming element shka which makes the word easier to deal with grammatically – but also makes it sound very Russian. Maybe it is this kind of integration into each language that makes these words sound less true to life and more varied from one language to another?

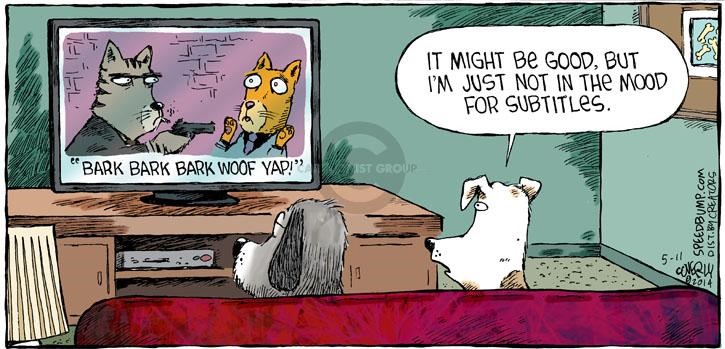

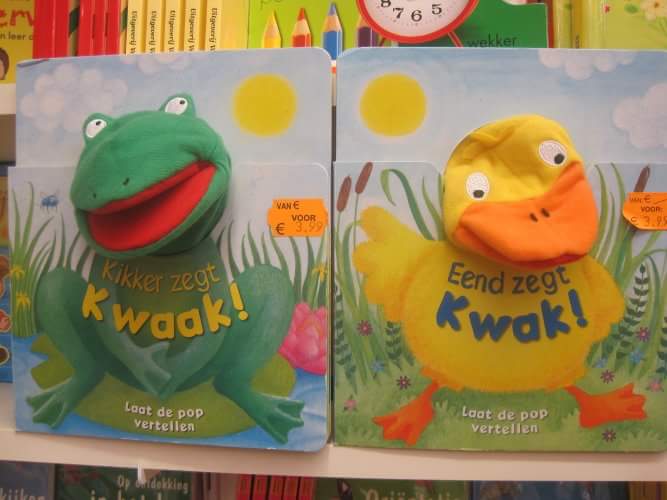

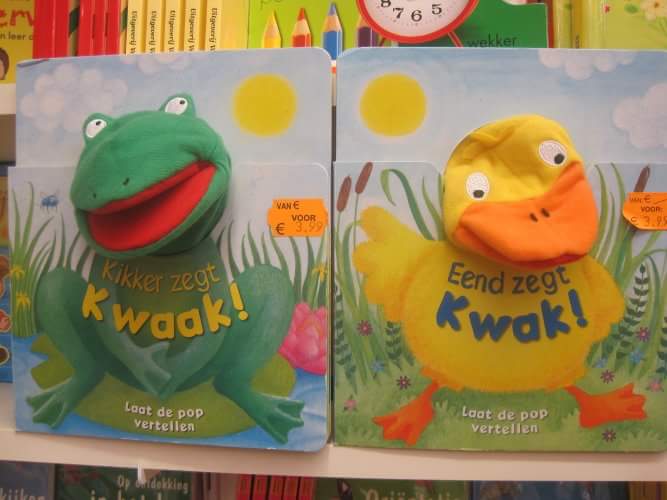

This is a start, but it must be far from the whole story. Animal ‘quotes’ like woof and cock-a-doodle-doo don’t need to interact all that much with English grammar at all. Nonetheless, they are clearly the English versions of the noises we are talking about:

And as we’ve already seen, the same goes for quack and oink. So even when it looks like we might just be ‘doing impressions’ of non-linguistic sounds, every language has its own way of actually doing those impressions.

Reassuringly, at least we are not dealing with a situation of total chaos. Across languages, duck noises reliably contain an open a sound, while pig noises reliably don’t. And there is widespread agreement when it comes to some animals: cows always go moo, boo or similar, and sheep are always represented as producing something like meh or beh – this is so predictable that it has even been used as evidence for how certain letters were pronounced in Ancient Greek. So languages are not going out of their way to disagree with each other. But this just sharpens up the question. For obvious biological reasons, humans can never really make all the noises that animals can. But given that people the world over sometimes converge on a more or less uniform representation for a given noise, why doesn’t this always happen?

In their feline wisdom, the cats of the Czech Republic can give us a clue. Like sheep, cats sound pretty similar in languages across the globe, and in Europe they are especially consistent. In English, they go meow; in German, it is miau; in Russian, myau; and so on. But in Czech, they go mňau (= approximately mnyau), with a mysterious n-sound inside. The reason is that at some point in the history of Czech, a change in pronunciation affected every word containing a sequence my, so that it came out as mny instead. Effectively, for Czech speakers from then on, the option of saying myau like everyone else was simply off the table, because the language no longer allowed it – no matter what their cats sounded like.

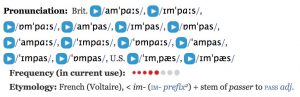

What does this example illustrate? First of all – as well as a morphology, each language has a phonology (sound structure), which constrains its speakers tightly: no language lets people use all the sounds they are physically able to make, and even the available sounds are only allowed to join up in certain combinations. So each language has to come up with a way of dealing with non-linguistic noises which will suit its own idea of what counts as a legitimate syllable. Moo is one thing, but it’s harder to find a language that allows syllables resembling the noise a pig makes… so each language compromises in its own way, resulting in nöff, knor, oink etc., none of which capture the full sonic experience of the real thing.

And second – things like oink, woof and mňau really must be words in the full sense. They aren’t just a kind of quotation, or an imitation performed off the cuff; instead they belong in a speaker’s mental dictionary of their own language. That is why, in general, they have to abide by the same phonological rules as any other word. And that also explains where the arbitrariness comes in: as with any word, language learners just notice that that is the way their own community expresses a shared concept, and from then on there is no point in reinventing the wheel. You don’t need to try hard to get a duck’s quack exactly right in order to talk about it – as long as other people know what you mean, the word has done its job.

So what speakers might lose in accuracy this way, they make up for in efficiency, by picking a predetermined word that they know fellow speakers will recognise. Only when you really want to draw attention to a sound is it worth coming up with a new representation of it and ignoring the existing consensus. To create something truly striking, perhaps you need to be a visionary like James Joyce, who wrote the following line of ‘dialogue’ for a cat in Ulysses, giving short shrift to English phonology in the process:

–Mrkgnao!

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by

But even when we discount this kind of thing, there are still plenty of disagreements remaining, and they pose a puzzle bound up with linguistics. A fundamental feature of human language, famously pointed out by