Fieldwork in Vanuatu

There are plans and then there are fieldwork plans. Sometimes everything does go without a hitch. This is not one of those times. The plan was to visit four different communities in Vanuatu who I had been working with over the last few years. I was there to donate the vernacular literacy materials we had created as part of our project and to run a teachers’ survey to find out what other resources and training they needed to teach the local languages in early years education.

The printers had sent the books a month earlier to Vanuatu – 14 large boxes weighing 15kg each. But by the time I arrived in Vanuatu the books had still not arrived. I checked the tracking number on the website and the books had been ping-ponged around different locations – India, China, Japan, Sydney, back to China and then Sydney again. Apparently the international shipping company tasked with the job couldn’t find Vanuatu on the map!

A few days later and still empty-handed with the books having not arrived, I was on the short plane ride to Santo Island followed by a three and a half hour tediously slow and bumpy truck drive to Agoru village, the largest village where the Merei language is spoken. Merei has just over 1000 speakers in a collection of villages between the Labe and Jordan rivers in northern Santo. There had been lots of rain, and the deep potholes in the unsealed road had filled with water. As we descended the steep muddy hill to cross the ford at the Labe river, I could feel the 4 wheel drive start to lose grip and ski down the slope.

Luckily, we made it in one piece! I stayed the night at Adam’s house, a Bible translator from Brisbane, who had been living there for almost twenty years. I met one of my good friends from my last visit – Melkio, and we went for a few shells of kava. Kava is the name of the plant piper methysticum, a type of pepper plant and the national drink of Vanuatu. The roots are peeled and then ground up and mixed with water to create a mildly intoxicating drink that relaxes your whole body. The next morning, we were off again to Vusvogo village – to the main event – Merei Day! This is a celebration to encourage the use of the Merei language and preserve their cultural heritage. I was hoping that lots of teachers from the different schools would be there so I could give them the digital copies of the literacy materials and conduct the interviews.

The journey itself was an adventure that I wasn’t properly prepared for. The last time I visited, the truck dropped me off close by, but this time the road was so muddy that the truck couldn’t get through. I hopped into the flat bed of the truck along with Melkio, Ishmael and Norman (two of the main bible translators who work with Adam), their wives, children and a few others. We were dropped off at the ford. We walked along the bank. It was easy going for the first few hundred metres before the track turned into a quagmire. The horse riders churn up the track, so the mud comes half-way up your shins. My flip-flops were not up to the job, and I had to go drae-leg ‘bare-footed (literally, dry-leg in Bislama, the national creole language of Vanuatu). It was slow going, and I made new friends in the best way possible, by humiliating myself – slipping and sliding all over the place. We got to the crossing point of the Labe river, by a small village. The current was strong, and the water came up to my chin – so we all had to swim across. We put our bags (and the babies!) in a large metal dish used for washing clothes, which three of the men carefully floated across the river. More mud and another, much easier river crossing, and we were at Vusvogo – after a three-hour mud-filled hike!

The event didn’t start until the next day. We piled into the nakamal, a low, long single-room traditional meeting house. One half for the men and the other half for the women. This is where we would drink kava, eat, sleep, and celebrate. My bed for the night was a woven pandanus mat on the hard mud floor. We drank more kava before I fell asleep listening to the women chat next to me and the obligatory hocking and spitting noise coming from the men drinking kava. The fire was kept stoked all night long, while a piglet poked its way in to the nakamal and was snouting around.

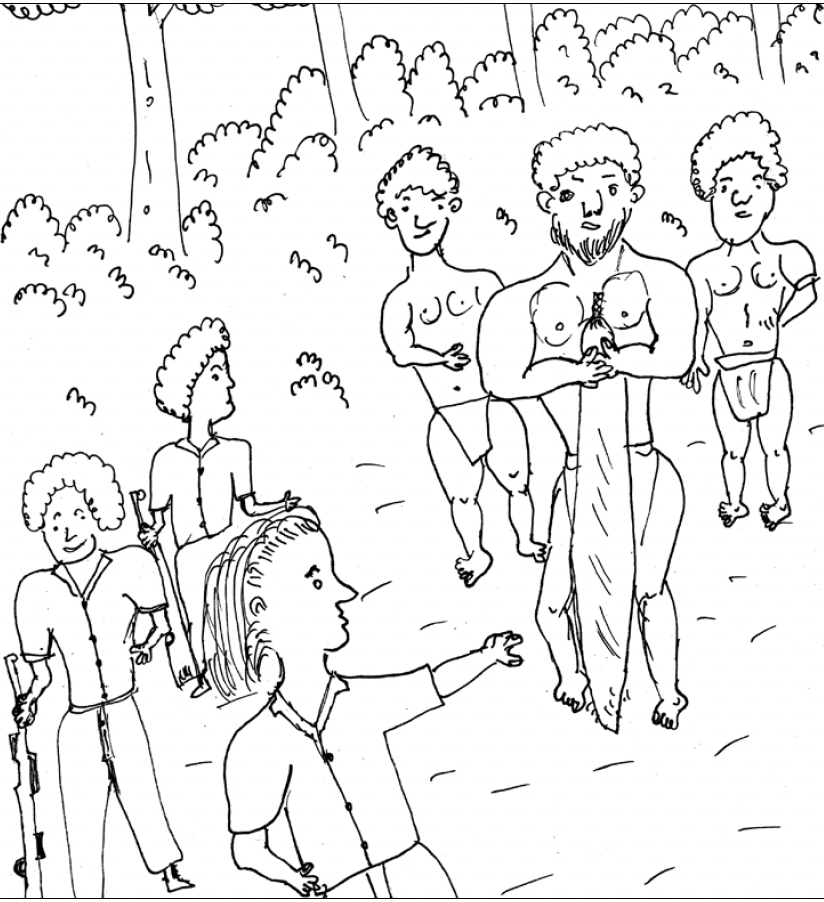

Breakfast was leftovers from the night before, stewed beef and rice served on a large pudding leaf (a bit like a banana leaf). I wandered over to the church and found Adam, Melkio, Norman, Ishmael, and Father Manuel. We drank sweet lemon leaf tea and we talked about different ways of promoting the use of local language in schools. I joined Adam at the back of the church. We both had the same idea, seeking out a little bit of comfort by leaning against the posts of the church. The Anglican sermon was all in Merei and a written version had been produced so I could at least follow the words, but not their meaning! A few hours later, we formed a procession back to the nakamal. Everyone was wearing their traditional clothes – loin-cloths for the men and leaf covering for the women.

Back at the nakamal everyone was giving speeches, The chief, the councillor, Adam and even I was asked to give an impromptu speech! I talked about my work with the community, the literacy materials I had made and the importance of keeping the language alive. Then the main event started – a smorgasbord of traditional food – taro, a starchy root crop, cooked in a myriad of ways. There was even traditional salt made from the ash of a particular tree. Every minute my name was called out Mike kam tastem! ‘Mike, come and taste!’. There was so much enthusiasm and pride in sharing their traditions. The main dish was taro nalot. Roasted taro was pounded by big sticks on a large flat wooden dish. The rhythmic pounding made the event even more theatrical as different beats rang out.

Then came a display of string figures, cats-cradle like figures made out of twine, followed by traditional dancing and games outside. The large buttress of a nakatambol ‘dragon-plum tree’ had been cut and used to cover a hole. Men in the centre beat the bass-drum, while singing, and other men and women danced in circles around them.

I found time to interview the teachers and share the digital copies of the books. They were all excited to use them and couldn’t wait for the hard copies. They had no literacy materials in their language before, except for an ABC poster. Hopefully, our materials will help start the move towards vernacular education in this community. As the sun set, I joined the men and drank kava until the milky way was clear in the sky. I fell asleep on the pandanus mat, only woken by that cheeky piglet snuffling about again.

The rest of my trip to Vanuatu went quite well. I managed to visit another two communities on the neighbouring island of Ambrym. But I got stuck in South-East Ambrym due to a flight cancellation and missed out on going to the fourth community on Epi. Back in the capital city, Port Vila, I was interviewed on local radio about my work and took part in a panel discussion at the national University about vernacular language education, as well as giving two talks at the Vanuatu Languages Conference. I also organised for three local language speakers from North Ambyrm, Vatlongos and Lewo attend a language documentation training session run by the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme in an effort to move towards more sustainable and community-driven practices in language docuemtation by capacity building with local experts. A busy, and mostly successful trip.

By the end of my six-week trip the books had finally arrived, only to be held up in customs while I organised a customs exemption from the Ministry of Education. And as I write this, three months after my trip, and four and a half months after the books started their journey, they are on their final leg of their journey – on cargo ships to Santo, Ambrym and Epi. It would have been wonderful to have handed out the books to each community myself, but things never quite go to plan with fieldwork.

I wish to thank Adam Pike, Melkio Wulmele, Willie Salong, Yanick Tekon, Loui and Gari Maki, Simeon and Madlen Ben, Helen Tamtam, Robert Early, Eleanor Ridge, Henline Mala and Andrea Bryant for all their help with the fieldtrip, the literacy materials, and their hospitality. Finally, a thank you to our funders, the ESRC and the University of Surrey’s Impact Acceleration Account for making our work possible.