Sign language mythbusters

We have all heard of sign languages. Most of us have seen people talking to each other using their hands and body movements instead of the voice: on the street, at a train station, or in a noisy café. We probably even felt a slight jolt of envy, thinking about how much easier it must be for them to communicate, when they are surrounded by loud music, laughter, and chatter. Curiously, however, very few people know what sign languages actually are. Unless you are a sign language user and/or a linguist, you probably have a lot of misconceptions about their nature. For this reason, linguists who write about sign languages, often begin their books with a discussion of myths and misconceptions. For example, Robin Battinson wrote a section on misconceptions about ASL, Trevor Johnston and Adam Schembri covered the same topic on the data of Australian Sign Language, Vadim Kimmelman and Svetlana Burkova discussed common mistakes in light of Russian Sign Language. Let us follow their example and bust a few myths!

Myth №1 There is only one sign language

Perhaps, the most mind-blowing thing about sign languages is that there is more than one. Indeed, if we never encountered sign languages in action, we most probably have a default assumption that there is one sign language, and everyone is using it. Why would you need more? Surely, at some point, someone came up with a list of signs for different objects and actions, and now all deaf and hard-of-hearing people use them.

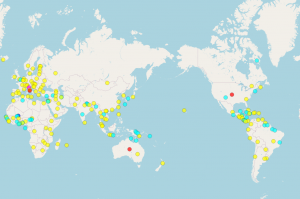

This is not true. Nowadays, we know about not one, not even ten, but one hundred and seventy different sign languages spread around the world. And it is very possible that there are other sign languages we are not even yet aware of. Check out the map from Glottolog, that provides a catalogue of the world’s languages:

Each dot in this map represents a language with its own vocabulary and grammatical structure. The yellow dots are sign languages that developed in urban settings. The blue dots are so-called ‘rural’ sign languages that appeared in small village communities with a high rate of hereditary deafness. Finally, the rare red dots are ‘secondary sign languages’. These languages developed in hearing societies as a substitute for spoken languages in certain situations.

Yes, 170 sign languages is a much more modest amount than roughly 6500 spoken languages, but it is definitely more than one. Now, let’s reflect on what sign languages actually are.

Myth №2 Sign languages are a kind of pantomime

Who likes Charades? In this classic team game, you need to enact a title of a book or a movie without saying a single word. Some of these titles can be quite tricky. Have you ever tried to mime “Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back”? So, we put forward our best improvisation techniques and we create quite complicated sequences of body movements in order to express the idea we need.

Sign languages do the same thing, don’t they? They express different ideas with movements of the hands and other parts of the body. So, maybe sign languages and pantomime are in fact the same thing? Well, no, not really. You see, one very important feature of a pantomime is transparency. We are usually able to guess what is going on without anyone translating it for us. Sign languages are not so generous. Try to make sense of this short video in Russian Sign Language. I can even give you a hint: the title of this video is ‘Miracles of dog training’.

A short story ‘Miracles of dog training’ in Russian Sign Language

If you are not familiar with Russian Sign Language, you probably didn’t understand that an unlucky man, the main character of this tale, tried to teach his dog to bring him a stick. The dog didn’t quite grasp the concept and instead started bringing him umbrellas, which it would steal from unsuspecting passers-by.

Why is it so hard to understand a sign language? Let me answer this with a counterquestion: why we would expect it to be easy? Well, this assumption stems from the phenomenon called ‘iconicity’. A lot of signs in sign languages look like what they describe. For example, if you watch the video about the dog training again, you will easily find a sign for ‘holding a stick in a mouth’. A tricky thing about iconicity, however, is that it is evident once you know what the sign means. But can you guess a meaning of an iconic sign? Let’s give it a go! Here is a sign in Russian Sign Language. Can you guess what it means?

An iconic sign in Russian Sign Language

If you are done guessing, here is the answer. This sign means ‘empty’. Once we know this, it seems obvious that a person in this video imitates looking for something in an empty bag. But it is really hard to guess it beforehand.

Another reason for the non-transparency of sign languages is that, unlike pantomime improvised on the spot, sign languages have quite complex rules for forming sentences. Speaking of sentences, let’s bust another widespread myth that has to do with sign language structure.

Myth №3 Sign languages are spoken languages articulated with hands

Many people assume that sign languages are not independent languages, but instead are signed versions of spoken languages. For example, British, American and Australian Sign Languages are signed versions of English, French Sign Language is a version of French, Russian Sign Language is a version of Russian, and so on. From this point of view, if someone wanted to express a sentence in English with something other than their voice, they could write it down or sign in instead.

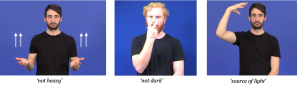

However, this is not the case. Many aspects of sign languages are completely unrelated to spoken languages that surround them. Trevor Johnston and Adam Schembri provide a good illustration of this using Australian Sign Language as an example. The English word light has several meanings, such as ‘not heavy’ (as in a light bag), ‘pale’ (as in a light colour), or ‘energy from the sun or lamp that allows us to see things’ (as in turn on the light). Although in English all these meanings are expressed with the same word, they would be translated to Australian Sign Language with three different signs.

Of course, this is not the only kind of difference between sign and spoken languages. Grammars are different too. Sign languages do not have articles, such as a and the in English, or case marking, like Russian Genitive or Dative. They don’t mark plurality and past tense with special endings. Instead, they have their own ways to express time and quantity related information. Many of them revolve around iconicity. But this is a topic for a different post. Stay tuned!