The headache-bringer-oner(er) of the English agentive suffix

Recently, a friend jokingly mentioned that he was thinking of hiring a light-turner-offer-onerer so that he wouldn’t have to get off the sofa to operate the light switch. In doing so, he made use of the extremely productive agentive suffix -er (also -or), which we use in English to derive a noun from a verb, to express the person or thing that carries out the action of the verb. The interpretation of this suffix is particularly transparent, even when used in completely novel ways, as in the recent article in The Economist newspaper cleverly titled The Baby Crisperer, drawing an analogy with The Horse Whisperer, while making reference to the gene-editing technology CRISPR-Cas9.

But the striking thing about the opening example is the multiple occurences of the agentive suffix. Most of the time in English the agentive suffix is simply added to the end of a word, regardless of whether the word in question has a single element (e.g. baker) or is a compound word (e.g. candlestick maker). But in the humourous example of the light switch operator, we are faced with a phrasal verb (or rather two phrasal verbs, turn off and turn on with the second instance of turn elided) and, in this case, the agentive suffix is added to each element of the phrasal verb. Omitting any of them (with the exception of the final -er, but we’ll come to that later) feels instinctively wrong (e.g. light-turner-offer-on, light-turner-off-onerer, light-turn-offer-oner, light-turner-off-on, light-turn-off-oner etc.).

So, just what’s going on here? Well, the issue lies in the fact that English phrasal verbs consist of a verb (which by itself has a different meaning) followed by a preposition or adverb, and it is precisely this ordering that appears to trip speakers up. In English, suffixes (by definition) come at the end of a word, but when a word has various elements to it, such as a compound word, there are multiple places that could potentially host a suffix. Since the meaningful element of many English compounds comes at the end (e.g. a houseboat is a type of boat that people live in, while a boathouse is a type of house for boats), it usually goes without saying that the suffix attaches to the final word, but if that ordering is upset in any way we tend to see different forms competing with each other (e.g. mothers-in-law vs. mother-in-laws, directors-general vs. director-generals).

Drawing a parallel with inflectional suffixes, which only affect the verb in a phrasal verb (e.g. wash up > he washes up > he washed up, pass by > she passed by > she’s passing by), we might expect the same to be true when it comes to the agentive suffix -er. Indeed, this is precisely what we see with established forms like passer-by (recorded in the OED as early as 1568). The historical form knocker-up (recorded in the OED from 1861), which referred to a person who would rouse workers by knocking on their window, also followed this pattern; it’s worth noting, however, that the form knocker-upper also exists, as seen in this BBC article about the profession, but it’s unclear whether this is a recent innovation or not. (NB. With the demise of this profession, readers can be excused for interpreting the term knocker-up(per) as a man with a predisposition for getting women pregnant.)

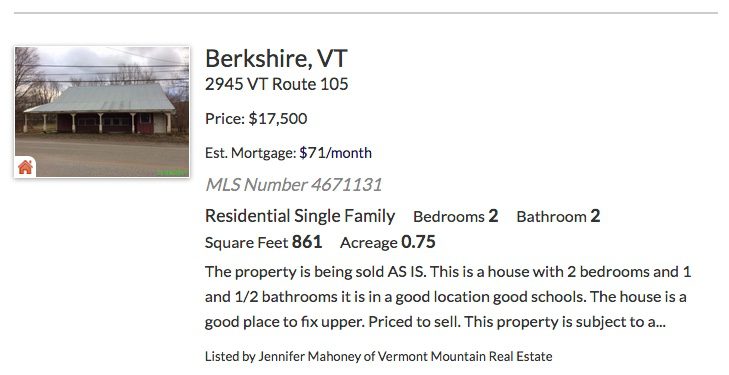

Other terms derived with the -er suffix, however, do not adhere to the pattern of marking only the verb element of a phrasal verb. For instance, we often talk of a property in need of renovation as a fixer-upper. Although we do encounter the forms fixer-up and fix-upper, fixer-upper is by far the most widely used term (recorded in the OED from 1948, and with 41 million Google hits, as opposed to fewer than 180 thousand hits for either fixer-up or fix-upper); no doubt the US reality TV show about home renovations, Fixer Upper, has helped popularise this term, in the US at least.

In many cases, a form which marks both elements of a phrasal verb co-exists with a form which marks only the first element of the phrasal verb, with the former appearing to be a much more recent development. Below are some examples of this (with dates showing the earliest recorded occurrences in the OED):

washer-up (1907) washer-upper (1961)

picker-up (1611) picker-upper (1913)

looker-up (1867) looker-upper (1934)

opter-out (1968) opter-outer (not recorded)

The form opter-outer was not found in the OED, but is sometimes encountered (a Google search results in around 100 hits), such as in this Telegraph article about opting out of a pension. The opposite term, opter-inner, results in a mere 2 hits, however suprising that might seem following last year’s barrage of GDPR opt-in-related emails that we were all subjected to. (Perhaps this reflects the fact that, in the pre-GDPR world, we tended to opt out of things, rather than the reverse?) One of those hits is this short web article, where the writer is bemoaning the amount of spam emails she receives; in it, she not only uses the forms opted-in and opter-inner – the former illustrating the fact that inflectional suffixes generally only attach to the verbal element of the phrasal verb – but also uses opt-in as a noun, stating that “not all opt-ins are created equal”, where the inflectional suffix is instead on the preposition.

But what’s even more interesting than the -er suffix appearing on both elements of a phrasal verb is that some speakers take this process one step further: once every element has been marked with the -er suffix, it’s as if the word as a whole then needs marking with the suffix again, leading to variants like washer-upperer, doubling up on the suffix on the final element. Based on Google searches, the form with the double suffix is surprisingly less common that I (as a speaker of British English) ever thought it was – washer-upperer returns a mere 244 hits on a Google search, while washer-upper returns 47,500 and washer-up returns 110,000 – although it’s entirely possible that in spoken language forms like this are much more frequent, and the Google search of what people are prepared to commit to writing are skewing the results. In any case, common or otherwise, such forms exist. OK, so no doubt some forms with a double -erer suffix are produced for humourous effect, as our opening example of the light-turner-offer-onerer was, but might there be an explanation for why speakers produce these forms in the first place?

One possible explanation is that speakers add the final -er by analogy with agentive nouns formed from verbs that themselves end in -er and which thereby end in the same -erer sequence, such as gatherer, plasterer, murderer? If this is the case, we might hypothesise that the first -er on the particle serves to make the phrasal verb ‘feel’ more verb-like (from the perspective of the suffix), giving the second -er which performs the agentive function something that it is happy to attach to. Could this possibly explain why Vermont Mountain Real Estate have listed a property on their books as being “a good place to fix upper,” perhaps mistakenly interpreting the -er suffix on the adverb as somehow forming a verb (maybe even a back formation from “fix upperer”)? (A much less interesting explanation, of course, is that this is just a typo.)

The locus of the plural marker -s in agentive nouns of this sort lends some weight to this idea. In forms that mark only the first element of the phrasal verb, such as passer-by and washer-up, the plural marker almost always attaches to the first element together with the agentive suffix, just as we would expect with inflectional suffixes (recall he washes up, she passed by), so we talk of the passers-by or the washers-up, but are less comfortable with the washer-ups (athough it should come as no surprise by now that both forms are found).

But if both elements of the phrasal verb take the agentive suffix, the plural marker attaches to the rightmost of the two (or more) suffixes. We can no longer say the washers-upper, but have to say the washer-uppers. When both elements take the agentive suffix, speakers appear to reanalyse the word as a single unit which no longer permits suffixes to occur internally (i.e. on a non-final element). And once it’s been reanalysed as a single unit, it almost seems right to then want to attach the -er suffix to the unit as a whole.

So while some may argue that this doubling up of the suffix is done intentionally, as a sort of metalinguistic joke, there are reasons to believe this isn’t always the case and that sometimes such forms (albeit markedly colloquial in nature) are produced because they just feel right and/or are following a rule in a speaker’s internal grammar.

Anyway, thinking about all this has brought on a headache, so I’m off to make myself an automatic day-maker-betterer(er)!