Cushty Kazakh

With thousands of miles between the East End of London and the land of Kazakhs, cushty was the last word one expected to hear one warm spring afternoon in the streets of Astana (the capital of Kazakhstan, since renamed Nur-Sultan). The word cushty (meaning ‘great, very good, pleasing’) is usually associated with the Cockney dialect of the English language which originated in the East End of London.

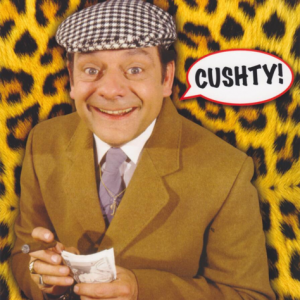

Check out Del Boy’s Cockney sayings (Cushty from 4:04 to 4:41).

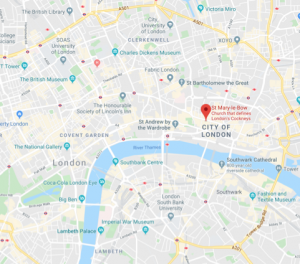

Cockney is still spoken in London now, and the word is often used to refer to anyone from London, although a true Cockney would disagree with that, and would proudly declare her East End origins. More specifically, a true ‘Bow-bell’ Cockney comes from the area within hearing distance of the church bells of St. Mary-le-Bow, Cheapside, London.

Due to its strong association with modern-day London, the word ‘Cockney’ might be perceived as being one with a fairly short history. This could not be further from the truth as its etymology goes back to a late Middle English 14th century word cokenay, which literally means a “cock’s egg” – a useless, small, and defective egg laid by a rooster (which does not actually produce eggs). This pejorative term was later used to denote a spoiled or pampered child, a milksop, and eventually came to mean a town resident who was seen as affected or puny.

The pronunciation of the Cockney dialect is thought to have been influenced by Essex and other dialects from the east of England, while the vocabulary contains many borrowings from Yiddish and Romany (cushty being one of those borrowings – we’ll get back to that in a bit!). One of the most prominent features of Cockney pronunciation is the glottalisation of the sound [t], which means that [t] is pronounced as a glottal stop: [ʔ]. Another interesting feature of Cockney pronunciation is called th-fronting, which means that the sounds usually induced by the letter combination th ([θ] as in ‘thanks’ and [ð] as in ‘there’ are replaced by the sounds [f] and [v]. These (and some other) phonological features characteristic of the Cockney dialect have now spread far and wide across London and other areas, partly thanks to the popularity of television shows like “Only Fools and Horses” and “EastEnders”.

As far as grammar is concerned, the Cockney dialect is distinguished by the use of me instead of my to indicate possession; heavy use of ain’t in place of am not, is not, are not, has not, have not; and the use of double negation which is ungrammatical in Standard British English: I ain’t saying nuffink to mean I am not saying anything.

Having borrowed words, Cockney also gave back generously, with derivatives from Cockney rhyming slang becoming a staple of the English vernacular. The rhyming slang tradition is believed to have started in the early to mid-19th century as a way for criminals and wheeler-dealers to code their speech beyond the understanding of police or ordinary folk. The code is constructed by way of rhyming a phrase with a common word, but only using the first word of that phrase to refer to the word. For example, the phrase apples and pears rhymes with the word stairs, so the first word of the phrase – apples – is then used to signify stairs: I’m going up the apples. Another popular and well-known example is dog and bone – telephone, so if a Cockney speaker asks to borrow your dog, do not rush to hand over your poodle!

https://youtu.be/MSbWz1PIJY8

Test your knowledge of Cockney rhyming slang!

Right, so did I encounter a Cockney walking down the field of wheat (street!) in Astana saying how cushty it was? Perhaps it was a Kazakh student who had recently returned from his studies in London and couldn’t quite switch back to Kazakh? No and no. It was a native speaker of Kazakh reacting in Kazakh to her interlocutor’s remark on the new book she’d purchased by saying күшті [kyʃ.tɨˈ] which sounds incredibly close to cushty [kʊˈʃ.ti]. The meanings of the words and contexts in which they can be used are remarkably similar too. The Kazakh күшті literally means ‘strong’, however, colloquially it is used to mean ‘wonderful, great, excellent’ – it really would not be out of place in any of Del Boy’s remarks in the YouTube video above! Surely, the two kushtis have to be related, right? Well…

Recall, that cushty is a borrowing from Romany (Indo-European) kushto/kushti, which, in turn, is known to have borrowed from Persian and Arabic. In the case of the Romany kushto/kushti, the borrowing could have been from the Persian khoši meaning ‘happiness’ or ‘pleasure’. It would have been very neat if this could be linked to the Kazakh күшті, however, there seems to be no connection there… Kazakh is a Turkic language and the etymology of күшті can be traced back to the Old Turkic root küč meaning ‘power’, which does not seem to have been borrowed from or connected with Persian. Certainly, had we been able to go back far enough, we might have found a common Indo-European-Turkic root in some Proto-Proto-Proto-Language. As things stand now, all we can do is admire what appears to be a wonderful coincidence, and enjoy the journeys on which a two-syllable word you’d overheard in the street might take you.