A picture is worth a thousand words: Choosing images for psycholinguistic research

Linguists need to come up with different ways of testing our theories of how particular languages in the world function. We generally rely on two main methods of data collection – linguistic elicitation and corpus collection. With linguistic elicitation a linguist asks a speaker of a language: ‘How do you say “Monty Python is really funny” in your language?’ But can we be sure that what the speaker said is naturalistic and not just a word for word translation?

Linguists need naturalistic data and can also record stories and conversations to build up a representative sample of a language (a corpus). This however takes a lot of time, effort and dedication on the part of both the linguist and the community of speakers of a language. It might even be that – after years of toil – the particular construction that a linguist wants to look at is under-represented with a dearth of examples in the corpus.

Thankfully, there is a happy medium! We can combine cognitive psychological techniques and targeted linguistic elicitation, to create scenarios where speakers produce naturalistic responses. Of course, this technique brings with it another set of problems entirely.

Psycholinguistic experiments need to be carefully designed and can’t be made up on the fly in response to something a speaker of a language says to you; this is drastically different to standard linguistic elicitation where one can continually come up with new sentences to check, while in the middle of working with a speaker of a language.

In our current research on optimal categorisation we aim to find out how different nouns are assigned to different classifiers in a group of six related Oceanic languages spoken in Vanuatu and New Caledonia. Each language has a different inventory size of classifying particles — from two to 23 — which are used in possessive constructions, and categorise the possession in terms of its use or functionality.

Here are a few examples from the Iaai language, spoken in New Caledonia, which has the largest inventory of classifiers in our sample of languages:

(1a) a-n wââ (b) hanii-ny wââ

FOOD.CLASSIFIER-his fish CATCH.CLASSIFIER-his fish

‘his fish (to eat) ‘his fish (which he caught)’

(2a) a-n koko (b) noo-n koko

FOOD.CLASSIFIER-his yam PLANT.CLASSIFIER-his yam

‘his yam (to eat)’ ‘his yam plant’

We want to see whether or not a particular noun that refers to a particular entity can occur with different classifiers, like with the words for ‘fish’ and ‘yam’ in Iaai above. Also, how does a language with 23 classifiers function differently from a language with just two or three classifiers?

One way in which we can discover how the classifiers function in each language is to use a card sorting experiment. These experiments present speakers with entities in the form of pictures. Speakers are asked to sort them into different groups, first in a “free sort” where they can create groups on any basis they feel is relevant and important, and second, in a “structured sort” where they are asked to group entities according to which classifier they would use in a possessive construction. By doing this with lots of participants we can see individual speaker variation in language usage in one language and across languages and get a clear sense of if and how a language’s classifier system is influencing the way that speakers think about and process different entities.

Once we have decided on which nouns to test in a card sort experiment we have to find or make pictures that represent these images. Sadly I don’t have the artistic skills of Michelangelo and won’t be painting any masterpieces for the experiment!

Choosing what type of image is trickier than it sounds as we are presented with an array of options.

First should we use simple line drawings of the images? The Noun Project has over 2 million small black and white line drawings. With such a choice of images we can find what we need. Here are some images of yams that I found on the site that we could use for our experiment.

These are great, and I know they are yams because I searched for images of yams on the website. But if I present these images to speakers I want them to tell me what they are. If the images aren’t instantly recognisable then participants will use different nouns to describe what they are seeing – is it a yam? A sweet potato? Manioc? Or some other entity? Actually, to tell you the truth, the third picture is actually a sweet potato! But it looks very similar to the first picture of a yam. Another problem is that these images can be quite abstract – and we can’t be sure that these symbolic representations of entities will be shared across different cultural and linguistic groups.

What about black and white pictures? – These are cheaper to print and easier to standardise. But we do not see the world in black and white and presenting entities as black and white pictures may make it harder to identify them, especially when the lightness of the background and the object of focus are similar. We need to be sure that the images we choose are easy to identify or else we can end up with problems of misidentification.

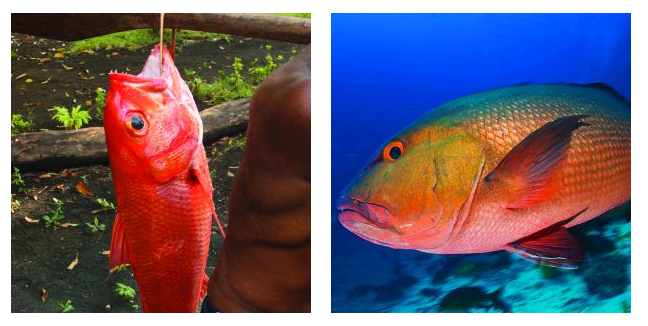

Another possibility is to remove the background of the image. By doing this we can eliminate distractions and help the participant focus on the object in the image. However, the background is often key. Background information gives context that can influence how the speaker of a language perceives the entity in the image.

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?

For instance, speakers may classify a fish that has been caught differently to a fish that is alive and swimming in the sea. The edible classifier is more likely with the former scenario, and a general classifier with the latter. But if we were to remove the background from both of these photos they would look strikingly similar! This leads us onto a very important question – what classifier would speakers of these languages use for a parrot if it was alive or dead?

So now we have decided to present images in colour and keep the background. But we must make sure that the background varies across different images. We don’t want participants to sort the entities into groups based on a colour or shape in the background or some other extraneous visual cue that may appear in several pictures!

For every psycholinguistic experiment that uses images there are multiple decisions that need to be made to figure out what type of image is required. The images we have chosen are specifically tailored to the nature of the languages we are studying to ensure that they are culturally relevant and thus identifiable.

For us, the pictures need to be realistic and represent the world around us — Sadly, we can’t take artistic licence with kangaroos and trampoline acts, as fun as that would be!